Good afternoon. This is the second of three lectures marking the sixtieth anniversary of the end of the old world.

Let me start with a persistent memory of a portent of things to come.

The night before, I had a nightmare. A salvo of missiles swept down through the darkness with fiery tails like those of comets. As they struck their target, Table Mountain exploded into a million fragments, sending a barrage of blazing molten shards up into the night sky and down into the bay. I woke to the dying echoes of my own screams, drenched in sweat, my heart pounding.

Some nightmares recur. This one didn’t; and yet I have recalled it practically every morning of the past sixty years. Rising from my bed I went to the window and looked up at the mountain, in bad weather a looming presence, on a sunny day, an old friend with a familiar wrinkled face. That nightmare came back to me and I gave thanks that it was no more than a bad dream.

And yet, what happened that first day was far worse; and what was yet to come was worse still.

Allow me to recap my first lecture. In it, I painted a picture of the world I lived in as a young man. It was a world of nations, rich nations and poor nations. Each nation was ruled by its own small rich and powerful elite, driven by greed and sustained by hubris. The nations had their differences with one another which sometimes led to war but, in essence, the rich of all nations controlled the world and its resources. The larger nations and also a few of the smaller ones had developed weapons of enormous destructive capacity called nuclear bombs. There were some four thousand of these, primed and ready to launch. The systems which were designed to control them were vulnerable to error and sabotage.

I showed you images and samples of the technology that enabled the rich to maintain their grip on power, including intercontinental ballistic missiles, the international space station and other satellites, aeroplanes, personal computers, television, smartphones, paper money, antibiotics and other drugs; and condoms. All of these became obsolete when the old world passed away.

Using maps I showed you what our part of the world looked like in those days. It was called the Cape Peninsula.

I lived in that old world for the first nineteen years of my life, so some of what I told you in my first lecture was based on memory; though not all. We did inherit at least one thing of value from the old world: the book. Books lived in libraries. Many libraries were destroyed but ours, where we are meeting today, survived. So, in preparing my first lecture, I was able to refresh and supplement my memory by referring to books.

My story this afternoon needs no books. It is based entirely upon my recollection of what happened sixty years ago this week, and in the months that followed.

That first morning I was sitting watching a soccer match on television.

My father was a professor of physics at this university. He was also the warden of a new ten-storey students’ hall of residence, Sol Plaatje Hall. It was well built. It is still standing down there, with two or three storeys exposed, depending on the tide.

We lived in an apartment on the top floor.

My father was in the conference room chairing a meeting of the hall staff, preparing for the return of the students after the summer vacation.

My mother came out of the kitchen and handed me her smartphone. She was also a professor. Her subject was geography.

“Yaw,” my mother said. “I’ve been trying to get Akosua all morning. No luck. Please try.”

Akosua was my elder sister. There were three of us, Akosua, Adwoa and me, Yaw. Those are Ghanaian names. My father and mother were both Ghanaians but the three of us were all born here. I grew up speaking English, but I can get by in Afrikaans and isiXhosa. Akosua was 24. She had finished a Masters degree and gone to London for a year to get some work experience and, I suppose, to have some fun. Adwoa was 22 and I was nearly 20.

The soccer match was at an exciting stage. I tried to reach Akosua but there was no reply. I guessed that she had switched her phone off or that her battery had run down.

Suddenly the television screen went blank and then the familiar face of a news announcer appeared. I groaned. I wanted to see the end of the match.

“We interrupt this broadcast with a breaking story. Reports are coming in of a series of major explosions at cities all over Europe and the United States. We’ll let you know as soon as we receive further news,” she said.

I paid no attention. Television in those days was full of violent events: terrorist attacks, wars and revolutions. My parents were interested in all that stuff, particularly my father, but I preferred sports.

The soccer match resumed, but a minute later the announcer was there again. I mouthed a silent curse.

“We interrupt this broadcast,” she said, “with live video footage which we are receiving direct from the International Space Station.”

The camera was aimed at North Africa and Europe. The image was clear; there were few clouds. Much of Europe was covered in snow. When we have our summer, they have their winter. Superimposed on the brilliant white background were five dark circular shapes, growing. Just then another appeared, quite suddenly, with a flash of fire.

They must have switched cameras. We now had an oblique view. Each object had a long stalk and a fluffy, cloudlike expanding head. The shape was familiar. I knew what they were, but the visual evidence was difficult to believe.

“Ma,” I called.

She came into the living room, wiping her hands on a cloth.

“What is it?” she asked.

Then she saw the image on the screen.

“My god!” she said and sat down next to me.

My mother was a church-goer. It wasn’t often that profanity escaped her lips. She pointed.

“Moscow! Warsaw!! Berlin!!! Rome!!!! Paris!!!!!”

Remember: I told you that her subject was geography.

Then: “London! London!! Akosua!!!”

She bowed her head, covered her eyes and began to sob. I couldn’t remember ever having seen her cry like that before.

“Ma, it’s alright,” I said and put my arm around her shoulder and hugged her.

Stupid. Of course, it wasn’t alright. But I was just a boy of nineteen. Still a teenager. Not yet twenty.

She wiped her eyes.

“Yaw,” she said. “Go and call your father.”

I called him. He wasn’t pleased. He said he’d be five minutes. I said no, he should come at once. That was the first time I’d ever contradicted him and I’d done so in front of his staff. His eyes narrowed. But he must have seen that I was close to tears, so he came.

As we entered the apartment he spoke to my mother in Twi. That was their language. I could understand a little but I never learned to speak it. When it was just the two of them, that is what they spoke. There was more than a hint of anger in his voice.

“Adeɛ bɛn?”

She didn’t reply, just pointed at the television screen.

“Holy Jesus!” he said.

My father poured libation to his ancestors but beyond that, he had no religion. He knew the bible well. But he regarded it as just a collection of stories; great stories some of them, but just stories. He was a scientist. He called himself a rationalist and a humanist. He rarely swore. His father, my grandfather whom I never met, was a Presbyterian minister. If my father had uttered a swear word when he was a child, he would have had his mouth washed out with soap.

“Christ!” he said.

“Akosua,” my mother said. “She told me she was going to spend the morning at the Tate Gallery, looking at paintings and sculptures.”

He took out his smartphone.

“It’s no use,” she said. “I’ve been trying for the past hour. Yaw too.”

Then she got down on her knees facing the sofa on which she had been sitting. As if to pray. But she didn’t pray, at least not aloud. She just beat the cushions again and again. I still remember the look of anguish on her face. Then my father got down on his knees, next to her, put his arm around her shoulders and held her tight.

Turning to me he said, “Yaw. Go to the conference room and tell them to wait. Tell them I’ll be with them in five or ten minutes.”

There were eight or ten of them sitting around the conference table. My Dad’s chair, of course, was empty. I knew them all, or, at least, they all knew me.

“Yaw, is everything alright?” asked Sarah Fortuin, Dad’s deputy, the one who actually ran the hall while he was busy teaching and researching.

What could I say? Clearly, everything wasn’t alright. They usually switched off their smartphones during a meeting, so as not to be disturbed by calls. As I was leaving, I heard Derek, the driver, say, “Heh, look at this.” I didn’t stop to learn what he had found on his small screen.

Dad and Mom were sitting on the couch.

“Yaw, switch on the recorder,” Dad said.

“Now come and sit down.”

The screen showed a new bomb site, an island off the northwest coast of Africa, one of the Canaries.

“La Palma?” I asked.

Dad nodded.

We had been there, on holiday, just a year before. La Palma was a volcano rising from the ocean floor, 4000 metres down, to a height of 2400 metres above sea level. A tourist guide had taken us to see part of a four-kilometre-long crack in the ground surface caused by a recent earthquake. He said that geologists predicted that the next earthquake would slice a huge chunk off the island and send it plunging down into the depths. This would generate a mighty wave—he called it a mega-tsunami—racing at eight hundred kilometres per hour towards all the cities on the rim of the Atlantic. As it hit land, the guide said, the wave might be as much as sixty metres high. Frightening! He delivered his well-rehearsed spiel with melodramatic pizzazz, laying it on real thick. We gaped. Dad gave him a generous tip.

Dad and Mom researched this afterwards and discovered that no serious geologist supported the story. We all had a good laugh at the way we had been conned. But now we had to think again.

We hadn’t begun to consider who or what might be responsible for the pandemic of exploding nuclear bombs. Truth to tell, we still don’t know. Some religious fanatic or crazy politician or soldier might have had some twisted motive for destroying one major city or even several, but why should this tiny island, with a population of less than a hundred thousand, be a target? It could only be because the evil genius responsible hoped to trigger that mega-tsunami, wiping out all the Atlantic coastal cities in one single economical blow.

Mom was still slowly, very slowly, coming to terms with the loss of her eldest child, my dear sister Akosua. But Dad’s thoughts had been diverted by the La Palma bomb.

“It’s ten,” he said. “The distance to La Palma is about 8000 kilometres. If the wave moves at 800 kilometres per hour, it will hit us at about eight this evening.”

Just then the announcer appeared on the screen.

“All major communication links with Europe and America have failed,” she said. “The President has issued a statement calling for calm. He says the government is in full control and no one should panic. We will share any further news with you as we receive it.”

“Idiots,” said my father.

Then he said, “The tsunami will destroy the City and sweep across the Cape Flats. We need to give the alarm.”

He paced the length of the living room, deep in thought.

“Kwaku,” said my mother, wiping her tears. “Slow down. Think. If there’s no tsunami you’ll look a complete fool.”

“You’re right. As always. But what’s the alternative? Do you remember the difficulty we had in getting to La Palma, via Accra and Dakar? It’s not a favoured holiday destination. We may be the only ones aware of the potential danger. If we say nothing and there is a tsunami, the death of thousands will be on our heads.”

When he returned from the conference room, he told us what had transpired.

“I set the scene for them,” he said, “and asked them for their advice. They all took the danger seriously. Those who live down on the Flats are going to bring their families to higher ground, just in case. They’re all busy phoning.

“Yaw, I want you to go to the supermarkets with Derek. Stuff the big van with whatever we might need, rice, canned foods, candles, matches, soap. Nothing perishable. Don’t bring it here. Derek will fill the van’s tank and then take the van with supplies to the upper campus. You come back here.

“I’m going to pass the buck. I’ll phone the vice-chancellor and ask him to call an urgent meeting of all the academic staff who are on campus.”

Then he said, “Adwoa. Where’s Adwoa?”

“She said she was going to meet a friend at the Waterfront,” I told him.

We tried to reach her on her smartphone but there was no answer.

“I guess she’s gone to see a movie and switched off,” I told them.

I was heading for the supermarkets. My father was going to see the vice-chancellor. My mother was on the edge of hysteria. Sarah came and sat with her. The images on the television were disturbing so we switched it off. There was one more essential job to do before we left. Dad called Accra. I heard his relief as his mother’s phone rang. Mom pulled herself together and spoke to her brother.

“Don’t waste a moment. Get in your car and head for the hills.”

I guess that many lives were lost in Accra that day. I hope that as a result of our calls our extended family there survived. But I don’t know. We never did hear from them again.

Events moved quickly. The vice-chancellor called the mayor. The mayor called provincial and national leaders. The police and the army and the radio and TV stations were mobilized. Soon there were long queues at banks and supermarket checkouts. Service stations began to run out of fuel. There were massive traffic jams as crammed cars made for higher ground. It was almost like a public holiday. Some sensible spirits drove to the Boland but many more made for UCT and Kirstenbosch. At UCT families spread rugs on the sports fields and when those were full the late-comers spilled onto what space was left on the campus roads. We made our temporary home in Dad’s office in the Physics Department. Adwoa found us there in mid-afternoon and took charge of Mom. Mom continued to try to reach Akosua even though we knew that there was no hope of ever seeing her again. Dad was busy, busy, busy, sitting in on meetings, planning, organizing. The satellite station continued to beam its pictures but they contained less and less information: the clouds from the individual explosions had coalesced, concealing the devastation below.

Our weather that day was perfect, clear sky, light south-easter. A day for the beach.

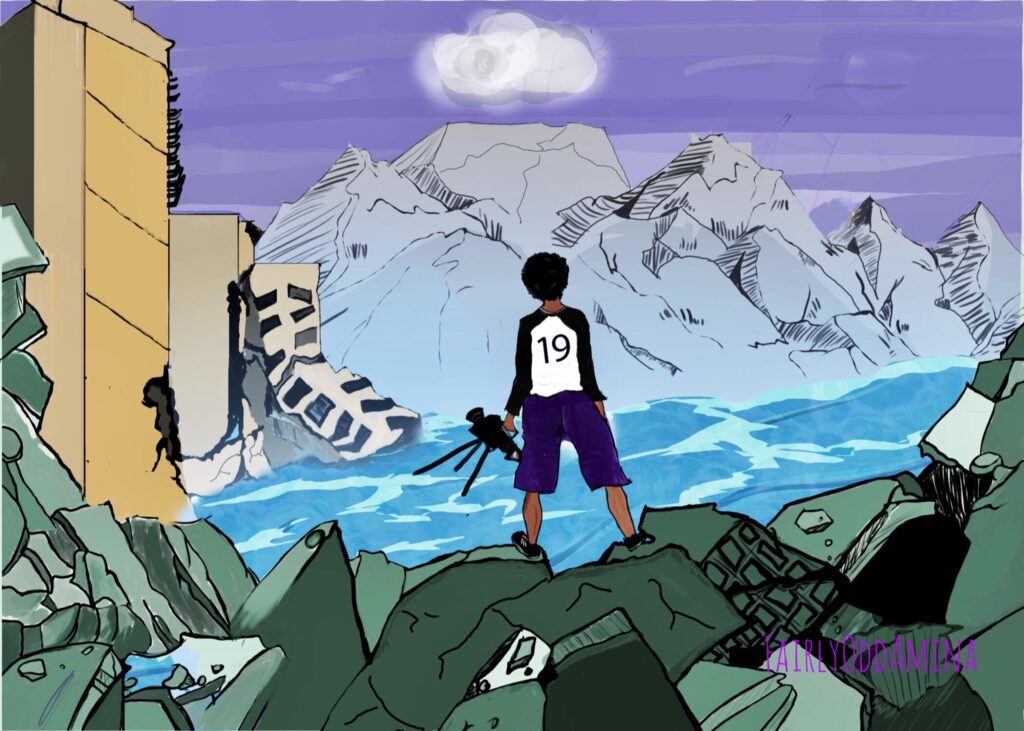

Dad sent me up to Rhodes Memorial with our cine camera. I was just in time to find a place at the low wall overlooking the Flats. Two wedding parties had come to be photographed but the crowd was too much for the photographer. I kept in touch with Dad and Mom and Adwoa, sending them pictures and videos over my cell phone. I scanned the Flats with my telephoto lens, picking out stragglers and looters. By this time everyone had seen the TV images. Strangers talked to one another. Some, like us, had lost family. All were deeply upset. A big guy next to me wondered aloud whether once the bombers had destroyed all the cities in the northern hemisphere, they would turn their attention to us. But there were sceptics too.

“This is a joke,” one loudmouth proclaimed. “This tsunami story is a ploy, invented by our corrupt leaders.”

The atmosphere was strange. We were waiting nervously for the opening of a performance which might or might not begin.

The sun disappeared behind Devil’s Peak and the shadow moved out across the Flats. The sea was calm. Robben Island was there, no doubt, awaiting its nemesis. Behind us, the steps were packed. The floodlights came on, illuminating the monument. Then almost at once, they went off. The crowd groaned in unison. But this was not the common power cut we had become accustomed to. Screams and shouts reached us from the mountainside. Then we saw it too. The great wave which was the tsunami came sweeping down from the north. It had struck the Koeberg nuclear power station, which supplied practically all the city’s electricity. That power cut was a portent of the dark future awaiting us. Having submerged Robben Island, the wave swept onto the City. There were shrieks as it passed through the Flats, destroying all in its path. Anguished voices cried out the names of suburbs: Milnerton, Maitland, Pinelands, Langa, Athlone, Hanover Park, Manenberg, Philippi. There was a mighty backwash and then the first wave was followed by another and yet another, not as high, not as strong.

For as long as I could remember, the Flats at night had been bathed in a sea of sparkling light; now there was nothing. Darkness descended upon our world.

I spoke to my father on my phone.

“Stay on,” he said. “Wait for the moon to rise and film what you can see.”

I ran the video I had taken on the camera’s screen. My neighbours gathered around. Our minds were numb. Then Christians began to sing hymns. I remember some lines from one of them.

“Away with our sorrow and fear!

We soon shall recover our home,

The city of saints shall appear,

The day of eternity come.”

Muslims cleared a space in the car park and performed a special, unscheduled salat.

“Allahu Akbar,” they called.

I had been chatting to the big guy beside me.

“I suppose that, for believers, religion is a comfort in a time like this,” I said to him. “What I don’t understand is how they can absolve the god they worship from responsibility for what we have just seen.”

That was a mistake. I learned then never to raise a religious issue with a stranger.

“What are you, an atheist?” he asked me. “This is the work of man, not God. God gave us free will and wicked men have abused it.”

He was bigger than me and older. I beat a retreat, choosing silence, just nodding my head as if I understood and agreed.

The moon came up revealing a scene of utter desolation. I shot my film and slipped away. The others were settling down for the night. They had nowhere else to go.

I stumbled down the mountain path, over the stile and into the UCT campus. My father had a large office. He had shunted his desk into a corner. My mother lay on the sofa, Dad on a camp bed and Adwoa on an inflatable mattress. The room was lit by two flickering candles. Mom made me an omelette on a small gas cooker. As I ate, I told them what I’d seen and showed them the video clips. Then I just lay down on a rug on the floor fully clothed and fell asleep… It had been a long day.

We woke at dawn to a new world. The campus was crowded with refugees. Leaving their families behind some set off on foot to see if anything remained of their homes. Others came to Jammy to join professors in a meeting called to assess the situation and formulate plans. The government and its agents, the police and army, were nowhere to be seen.

My father sent me with Derek to report on the condition of the South Peninsula. It was another glorious day. There was little traffic. The drive down through Constantia was as beautiful as I had always known it. It was easy to imagine that the events of the previous night were just a bad dream, like my nightmare. Then, as we reached Tokai there were patches of standing water where none had been before. Pollsmoor and the golf course below Steenberg were flooded. On the pavement of Boyes Drive cars were parked bumper to bumper. The tarmac was packed with families, camping. We parked the bakkie and walked. The night before I had seen the devastation of the northern suburbs by moonlight. This was worse. I knew Muizenberg quite well. I used to go there at weekends to surf. It had just one multi-storey building, an ugly block of flats. That eyesore was no more, not even an identifiable pile of rubble. The suburbs where all these people had had their homes had been wiped from the face of the earth. You might have heard your grandparents mention their names: Marina da Gama, Vrygrond, Lavender Hill, Retreat, Grassy Park, Montagu’s Gift.

A young man heard our astonished exchanges.

“Where have you guys come from?” he asked.

I told him.

“Did the tsunami come right through here from Table Bay?” I asked.

“No man,” he said. “We had our very own tsunami. Imported from Indonesia, I reckon, like our ancestors. It came late, two, three in the morning, after the moon had gone down. It was only when the sun came up that we saw the full damage. Take a look with your binoculars. Total destruction, all the way to Mitchells Plain, Khayelitsha, Strandfontein, the Strand, Gordon’s Bay and miles inland. Man, tell me, what are we going to do? We brought food with us, just enough for a few days. And then?”

His wife or girlfriend came up and took his hand in hers. She was pretty. After sixty years I can still see her face, the tears in her eyes. I could have fallen in love with her if she hadn’t been taken already. She didn’t say a word, just shook her head again and again, as if she couldn’t believe what had happened.

I tried to imagine the scene in the early hours of the morning. There would have been no warning. This “Indonesian” tsunami must have wreaked havoc on its way to us: Maputo, Durban, East London, P.E, Knysna, Mossel Bay. The mouth of False Bay would have acted as a funnel concentrating its force. East of Muizenberg, nothing would have stopped it in its path across the Flats. But to the west, the all but irresistible tsunami must have met its match in the immovable mountain and bounced right back into the sea. The scene below told the story. The lower half of Jacobs Ladder at St. James was no more. The fancy houses of the rich on the upper slopes above the high water mark had survived unscathed. But they were now inaccessible from the Main Road which, together with the railway line, had been washed into the bay.

Yet now all was peaceful. The sea had no memory of what had taken hold of it only hours before. The lines of surf rolled in and broke on the rocks along the shore. Somehow, the tidal pools at St. James and Kalk Bay and the walls of the fishing harbour had survived; but the boats were gone.

We got back to UCT after dark, tired, hungry and depressed. Adwoa had been to town. She reported that the wave had destroyed the Gardens, flooding Parliament and ruining the contents of the National Library.

The next morning dawned fine again but my father explained that we were working to an unknown dark deadline. Winds in the upper atmosphere, he predicted, would soon distribute the nuclear cloud. The earth would soon be wrapped in an opaque radioactive cocoon. We had to move the folk camped out on the sports fields indoors before that happened.

It wasn’t easy. The communications on which we had depended were no more: no TV, no radio, no smartphones. We had to adapt. And quickly. The campus was a hive of activity. Jammy was the nerve centre. There were committees to allocate accommodation and fuel and plan the distribution of water and food. A trauma centre started giving advice and support to the many who needed it. The dead had to be identified, if that were possible and then quickly buried. So much to do, so little time. But there were many willing hands.

On the third night, I sat in the dark on the Jammy steps with Adwoa, remembering Akosua and chatting about the events of the past three days. Above us, Orion and the Southern Cross were bright and clear.

The next morning the sun failed to rise. That’s not true, of course. It must have risen, but to us it was invisible. A dark impenetrable cloud had enveloped the earth. While my father had power from the solar cells on the roof, he’d used it to print thousands of fliers with advice about the dangers of radiation. The darkness would pass, he promised, but until it did, no one should go outside. In every building, a responsible person should lock the outer doors and hide the keys.

In his lab, my father had two heavy anti-radiation suits, complete with hoods and gloves and boots. He put one on each morning and went for a walk with an instrument called a Geiger counter which, when switched on outside, emitted a series of rapid pings. When the pings slowed down, he told us, it would be safe to go out.

Picture us on this campus, thousands of refugees, all locked up in our separate buildings, in total darkness. Although it was still summer, it was bitterly cold. There were bound to be emergencies, a shortage of candles, a blocked pipe, an ill child, and a death. Once a day a messenger did the rounds, collecting and delivering urgent messages. That messenger was often me, wearing one of Dad’s suits. And if someone, a doctor or a plumber, had to move from one building to another, I would deliver the spare suit to him.

At least that made a change from the tedium. There was little to do. Until the bottled gas ran out, cooking consisted of warming tinned food. Water was reserved for drinking and washing hands. For two months we didn’t wash our clothes. We stank! The main problem was to keep our minds occupied. Candles were strictly rationed, so we couldn’t read. Dad organized lectures and storytelling sessions and debates. Those two months brought out the best and worst in us. Some were afflicted with anger or despair; others discovered skills as leaders and healers. Outside, black rain fell, loaded with radioactive dust. After a rainstorm the Geiger counter pinged and pinged.

At long last, the cloud thinned and a hazy sun appeared. The solar cells on the roof began to charge our batteries and we had light at night. Dad announced that we might go outside for an hour a day.

During the time of darkness, my sister Adwoa and I had become good friends. On our first morning out, we decided to go up to Rhodes Memorial. It was a shock. The trees were naked and the shrubs and bushes and wild grass had all died in the darkness. This captured our attention and it was not until we reached the Memorial that we looked out over the Flats. Try to imagine our astonishment. Table Bay and False Bay had joined in marriage. Judging from the buildings protruding from the water, the sea level must have risen ten metres. And that was the least of it. Both bays were full of icebergs, thousands of them, as far as the eye could see.

“What on earth?” was all I could say.

Adwoa, a scientist like our parents, had the answer.

“My guess is that some of the bombs were directed to the Antarctic Ice Shelf. It must have broken away. This is the result.”

In the two years that followed, those icebergs became smaller and smaller and fewer and fewer and eventually disappeared. They just melted into the ocean and as they did so, the sea level rose and rose. What had once been the Cape Peninsula became what we all know well, the two islands we call Hoerikwaggo and Autshumao.

That seems an appropriate point to bring this lecture to a close. In my last lecture, I shall tell you something about the years after this disaster, a period which started with no government, no police, no fuel, no salaries, no banks, no money, little food, bad water. It was on that shaky basis that we set out to build a new society, different from that of the old world, a society based not on greed and concentrated power but rather on fellowship and mutual help, a society in which today we all have work and in which we all share the rewards of our labour.

Now: any questions?

END