The only son of thirteen children, Obera was raised oblivious to brutality despite his brawn. His only job was to be paraded around the market as the prize feather in his peacock mother’s plume. His mother was only satisfied when the swoons about his tawny eyes reached the ears of Ruoth’s daughter. Everything else was done for him by one of his sisters. Achiel thatched and cleaned his dala. Ariyo hunted and slaughtered the animals he then presented at village feasts as his triumphs. Adek chopped and collected firewood. Ang’wen cooked for him. Abich nursed him when he fell ill and Auchiel guarded him at all costs.

Experiencing brutality earns you foresight. If Obera had any, he would have heeded Ja’Chien’s warning. On one of the days he strutted around the market, past Ja’Chien, who sat on a three-legged stool rumbling about omens — he should have stopped and listened. The plague struck first, swift and lethal like a bolt of light, leaving behind a carnage that included his entire family. The famine came next, an endless rumbling, that devoured everything, leaving only dust.

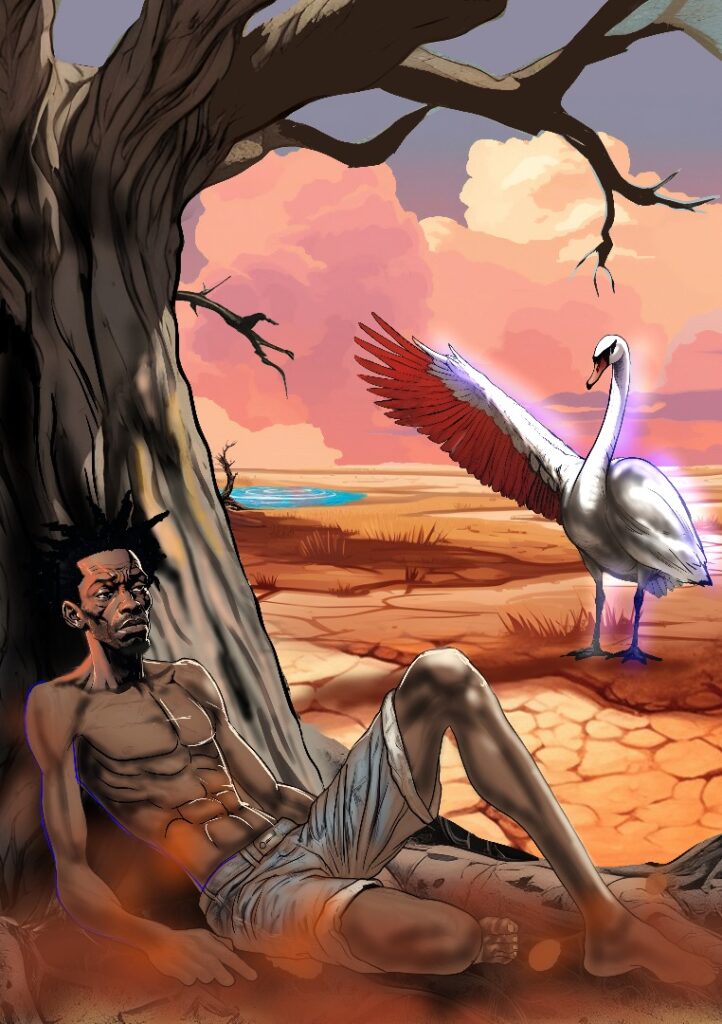

Obera sat under the mango tree, waiting to die. The once-lush tree was now bare and decrepit, ready to crumble at a hair’s whisper of the wind. Obera leaned his spine-protruding back against the trunk, melting into it under the smoldering heat. As he gathered the strength to exhale for the last time, he waited to see his mother, just as his sisters Abriyo, Aboro, and Apar had before they passed away. Instead, he saw a mirage in the arid deadlands before him, which had once been an opulence of wheat and corn.

The mirage slithered towards him in a haze. Once in front of Obera, the haze cleared, and a majestic swan emerged from a pool of water. The swan approached him, spreading its left wing and brushing it over the water’s surface. It ruffled its dripping feathers over Obera’s cracked lips, then gestured to the pond.

“Drink.”

Obera scrambled to the water, plunging his whole face into it. The water was sweet, fresh, and cooling. He drank, relishing it as it cascaded down his scratched throat, into his belly, and through his veins. Obera trembled from the new surge of energy as he gathered more water into his cupped hands, slurping and gulping, desperate to quench his thirst as quickly as possible. When he had drunk enough water to bulge his stomach like a taut gourd, he fell back against the tree.

“It’s only a matter of time before the sun claims every drop of my water.”

Obera opened his eyes and lazily gazed at the Swan. It had stretched its graceful neck to the sky, worry gleaming in its eyes. Obera kept his eyes steady on the swan, afraid that if he looked up, he would lose his illusion and everything would disappear, including the water that now made his blood wet again.

“Please, Jatelo. Look after my children. When the waters dry, they will be exposed to the kites lurking in the winds.” The swan opened its right-wing slightly to reveal eight large, smooth, silver eggs.

It began to dawn on Obera that this was not his imagination.

“Jatelo, please look after my children. Keep them safe in your homestead and when the rain arrives nine days from today and my waters are replenished, I shall come and collect them. If you do this for me, I will reward you greatly. I will give you riches beyond that of any other man on this land. Riches that will bring Ruoth’s daughter to your dala.”

Obera perked up at the mention of Ruoth’s daughter, whose beauty was so ethereal not even a plague and a famine could taint it.

“It is a promise. Leave your children with me. I shall take care of them and protect them.”

If only Obera had paid attention to the old lady that sat on a mat in the market telling siganas to the children while she weaved baskets to sell, he would have known to never trust a swan with scarlet under-feathers.

A moonless nightfall settled over his dala like a velvet cloak. Obera went to where Ag’wen had built the kendo and carefully placed the swan eggs in it, covering them with the bits of thatched roof that had loosened and collapsed to the ground. When he was satisfied that the eggs were safe, he realized that he had nothing to eat. It was too dark to scavenge for termites and crickets. Usually, he did his scavenging at dawn before the scouring sun yawned. However, today he had not planned to make it through the day. He caressed his stomach once again. Thinking about the coming rain. Had the Swan said eight days or nine days? He crawled over to what was left of the Cyprus mat Achiko had weaved for him. He drifted to sleep with thoughts of boiled corn and grilled fish wafting through his mind.

The sound of crying stirred Obera awake. His hand reached for the spear under his mat, and as stealthily as he could, Obera slowly turned to the sound. It took a moment for his eyes to adjust and outline a form, a human form hunched over the kendo. He tightened his grip on the spear, carefully rising to his knees.

“Mayo-weh, mayo-weh! What is this, my brother Obera? The kendo is cold.”

It was the voice of his sister Ang’wen. She was lighting a fire in the kendo. Obera tried to stand, but his knees buckled and he collapsed. “Ang’wen put out that fire at once!” he cried, his voice still hoarse with sleep and starvation.

Agn’wen had already placed the pan over the heat. “You must eat, Obera. Look at you, you are nothing but bones and skin. How can I rest properly when you are not eating?”

Agn’wen took one of the eggs and before Obera could protest, she cracked it over the pan.

“You must not Ang’wen I made a promise. You must not.”

It was a weak protest. The aroma was filling the little hut, igniting a ravenous growl from the pits of his belly. He crawled over to the pan, grabbing a handful of the sizzling scrambled egg, his calluses preventing the heat from scalding his fingers.

The following morning, Obera woke up to find himself lying by the kendo with the taste of his broken promise still lingering on his tongue. Guilt washed over him. The eggs were unearthed and exposed. He counted and counted again, always arriving at seven remaining eggs. He remembered the promise of riches.

“Ang’wen, that foolish girl. Always trying to fatten you up like a cow for slaughter!”

Obera looked up to see the outline of his mother’s shadow filling the entryway into the hut. “Hae-hae!” she clapped her hands.

“Forbidden fruit is sweet on the eyes but bitter on the tongue, you will learn.”

“What should I do?” Obera pleaded with his mother.

“Take the shards of eggshell and go to the riverbed. The river no longer flows but the spirits still dwell there. Look for where the potter dwells, dig a shallow hole, place the shards in the hole then cover it. You must offer his spirit-fermented nyuka. Once you cover up the eggshell, pour the nyuka over it. When the sun has set completely, you can dig up the egg.”

“Can the potter save the egg?”

His mother kissed her teeth. “Don’t be foolish! What magic can take food you have already digested and return it as it was? It will be nothing but an empty shell.”

“But Mama, where will I get fermented nyuka?”

Obera found the clay pot covered with cow skins behind his father’s dala buried so deep that the soil was still cool beyond the blistering sun, exactly as his mother had told him. The nyuka was beyond fermented. It was rancid, but would a spirit get an upset stomach? Obera balanced the pot over his head as he had seen his sisters do, careful not to let even a drop of it fall on him despite his buckling knees. The riverbank was not far from Obera’s dala. As he made its way there, his mind drifted to the time when the palpating river flowed through it. How the spirits rising at sunset would ire the water, causing it to rage through the village, thrashing about. They were always warned never to go near the river when their shadow was stretched to its fullest or they’d be dragged in by the restless spirits.

Obera found the dwelling place of the potter’s spirit where his mother said it would be, where the sand shimmered like it was hiding crystals. Obera followed his mother’s instructions and waited for the sun to set to unearth the egg. He gasped with awe at the sight of the silver egg. Whole and smooth, just as it was. He gently lifted it, testing its weight on the palm of his hand. It felt full. Obera resisted the urge to crack the egg and see what was inside. He picked up his spear and the remaining pot of nyuka and made his way back home.

That night Obera had a dream of a feast of all his favorites. Coconut fish stew, roasted sweet potato, boiled corn on the cob, sweet ripe guava and mango, roasted peanuts. When he woke up at the crack of dawn, he found himself lying by the kendo, next to a cracked egg.

Every night for the next week Obera had the same dream. Every morning, he woke up beside a cracked egg. Every evening, he replaced the cracked egg with one the potter spirit made. Until all eight eggs had been replaced.

On the ninth day, it rained. Then it poured. The river came back; the grass began to grow and the Swan arrived at Obera’s dala. The Swan seemed oblivious to Obera’s trembling hands and beads of sweat condensed on his forehead despite the cool winds that came with the rain. She unsuspectingly gathered her eggs under her wings and handed Obera eight quail-sized solid gold eggs.

Obera became the wealthiest man in the land. Finally, he was invited to Ruoth’s dala.

Obera was preparing for this visit when the Swan appeared, feathers ruffled with woe.

“My children!” It shrieked, tossing itself around the dala. It snapped its beak at anything it could find. His farming and hunting tools, his spear, his shield, his fence -leaving angry marks and cracks. It threw its neck at his growing corn, uprooting them. It kicked his hen pen, sending the chickens scurrying around the compound. “Where are my children?” The Swan demanded as it crushed their eggs under its talons. “You ate them! You ate my children.” Its voice was shrill with ire, its head lifted to the heavens to call on the gods of vengeance.

Obera stood still, too stunned to say or do anything as the Swan wept.

“One day you will know this pain,” the swan said, her hoarse voice barely above a whisper, and with that, the night swallowed the Swan.

Obera sent harvest and cattle to Ruoth’s house, staying behind himself with an excuse of ailment. He was unable to sit still, pacing up and down, wringing his hands, and mumbling to himself until Achiko materialized before him. He sighed with relief at the sight of his most levelheaded sister.

“Obera, you are stomping on my grave. I cannot even rest.”

Obera relayed his predicament to her. Ochiko listened quietly, her calm demeanor sedating his nerves.

“This Swan appears to you when you are on the brink of dying of starvation. Smells like a mbuta.”

“What should I do?” Obera pleaded.

“Go and see Ja’Chien. He’ll know what to do.”

Obera arrived at Ja’Chein’s dala at the first crow of the rooster.

“Ah, it is a chun-mar-kech,” Ja’Chien rubbed the stub on his jaw as he spoke, having recognized the sort of spirit that had sworn vengeance on Obera.

There was a glint in Ja’Chien’s eye as he asked Obera to describe every little detail about the Swan. After hearing the whole story the old man began to speak.

“They are evil tricksters. Attracted to hunger like flies to meat. They appear before you at your most desperate and trick you so they can devour your children. They give you wealth so you will marry and have children that they can then claim. They appear in many forms and if you take any food or drink from them, you will be cursed by a ravenous hunger that you will not be able to resist.”

Obera covered his face with trembling hands. “What have I done?”

“I know what’s worrying you. I know you were supposed to present yourself as a suitable suitor for Ruoth’s daughter, Asumu. Now you fear you cannot go through a marriage with her.”

Obera gave a weak nod in response.

“Listen, why don’t you marry Awilo, Nyar-Omollo? The plague took her husband before she bore a child. Her husband’s father was your sister’s Adek’s father-in-law. If you took her in as your first wife, everyone will understand that as an act of duty and kindness. She will bear the children for you, and you can take Asumu as your second wife.”

Obera scoffed. “Ruoth would never allow his daughter, his only child, to be the second wife of a homestead.”

Ja’chien’s booming laughter rumbled over the dala. “Asumu cares about three things only. Her beauty, her pride, and her wealth. Do not worry, she will be more than willing.”

Awilo was a small woman who barely came up to Obera’s chest. She was not tall like Asumu who could lay her head on his shoulder. Everything was wrong with Awilo. Her eyes were uncomfortably large on her small face, and it reminded him of a Tarsier. Her soft, husky voice did not fit well with her petite frame. She smiled readily unlike Asumu. Awilo’s beauty was shy and would only reveal itself when she thought no one was watching. Her gaze when she daydreamed under the mango tree. The tilt of her head when she was unsure. The hum of her song when she was in a good mood. It began to seep into Obera, soaking him with her essence, and sinking him into a pool of love.

“I’m with child,” Awilo whispered. It was a year after they had gotten married. The moon was high in the sky and Obera held her so close to him he felt the steady rhythm of her breath. He turned her to face him and kissed her softly.

“It will be a daughter,” he declared.

“It will be a son,” she countered as she placed her hand over her belly possessively.

“I had twelve sisters. It will be a girl,” he assured her, playfully shooing her hand off her belly and replacing it with his own.

“I had five brothers. It will be a boy.” Awilo looked up at her husband as she spoke, narrowing her eyes in feigned protest.

They laughed, then kissed, then laughed again. After all, did it really matter? Obera had every intention of giving his firstborn plenty of brothers and sisters.

Obera would not allow his wife to do anything but rest and eat. He followed her around the house, taking the sisal broom to clean, the jembe to go and farm, the firewood to get the kendo going and cook. Whatever she craved, he would go and hunt for it. Whatever she needed from the market, he would run and get it. His sisters no longer came to see him, but he knew they must be cackling at him from beyond.

It was a boy. A boy with Awilo’s large eyes and Obera’s broad smile.

Awilo had placed the boy on a mat under the mango tree and went inside the hut. Obera, who had been harvesting, took a break to watch the child till his wife came back out. A shadow cast over Obera, He looked down to see the outline of a wingspan, and his eyes shot up to see a crimson bird rapidly descending towards his son. Obera ran with all his might, shouting desperately at the bird. The bird reached the child and swooped it up. And with their beloved son caged between its talons, the bird disappeared into the haze of the rising sun.

Their second child, a son, was taken at the market and their third child, a daughter was grabbed from Awilo’s arms.

“I am with child,” Awilo said, her voice dead from the exhaustion that comes after grief. Obera nudged her to turn and face him when she did not, he pulled her closer to him and kissed the back of her head. “Nothing will happen this time. I promise.”

“We cannot lose another child; it will break my wife.” Obera pleaded. He had come to see Ja’Chien, his third such visit. He had come after his first child was taken but Ja’Chein was traveling. When he came again after his second child was taken Ja’Chien was still away.

Ja’Chein rubbed the stub on his jaw. He reached into his snake-skin bag and retrieved a wooden, carved doll.

“I have traveled very far and encountered many tribulations to get my hands on this. Obera, you must be ready to compensate me well for my troubles. It is a doll carved from a dead hollow tree, a tree that harbored the souls of innocence.”

Ja’Chien filled a clay pot with water and added three drops of Obera’s blood. He then placed the carved doll in the pot and covered it.

Awilo gave birth to their fourth child, a daughter. Ja’Chien had sent a midwife to take care of Awilo. Awilo refused to have her daughter out of her sight for even a second. She didn’t trust anyone and made sure the child was always attached to her hip.

The bird came for the child in the dead of the night. Awilo woke up to find the arms that had cradled her child the night before were now empty. Her scream was gut-wrenching.

Obera rushed over to Ja’Chien’s house. On his way there he spotted The Chun-mar-ketch heaving and choking by the river. The spirit gargled, sputtered then fell to the ground dead. Obera watched as it disintegrated into the air, leaving behind the half-devoured wooden doll.

Ja’ Chien handed the child to Obera. A girl with Awilo’s round eyes and tender smile. He ran over to his dala. By the time Obera arrived, ready to show Awilo that he had kept his promise, that he had saved their child and their future children, he realized that his wife had long since breathed her last.