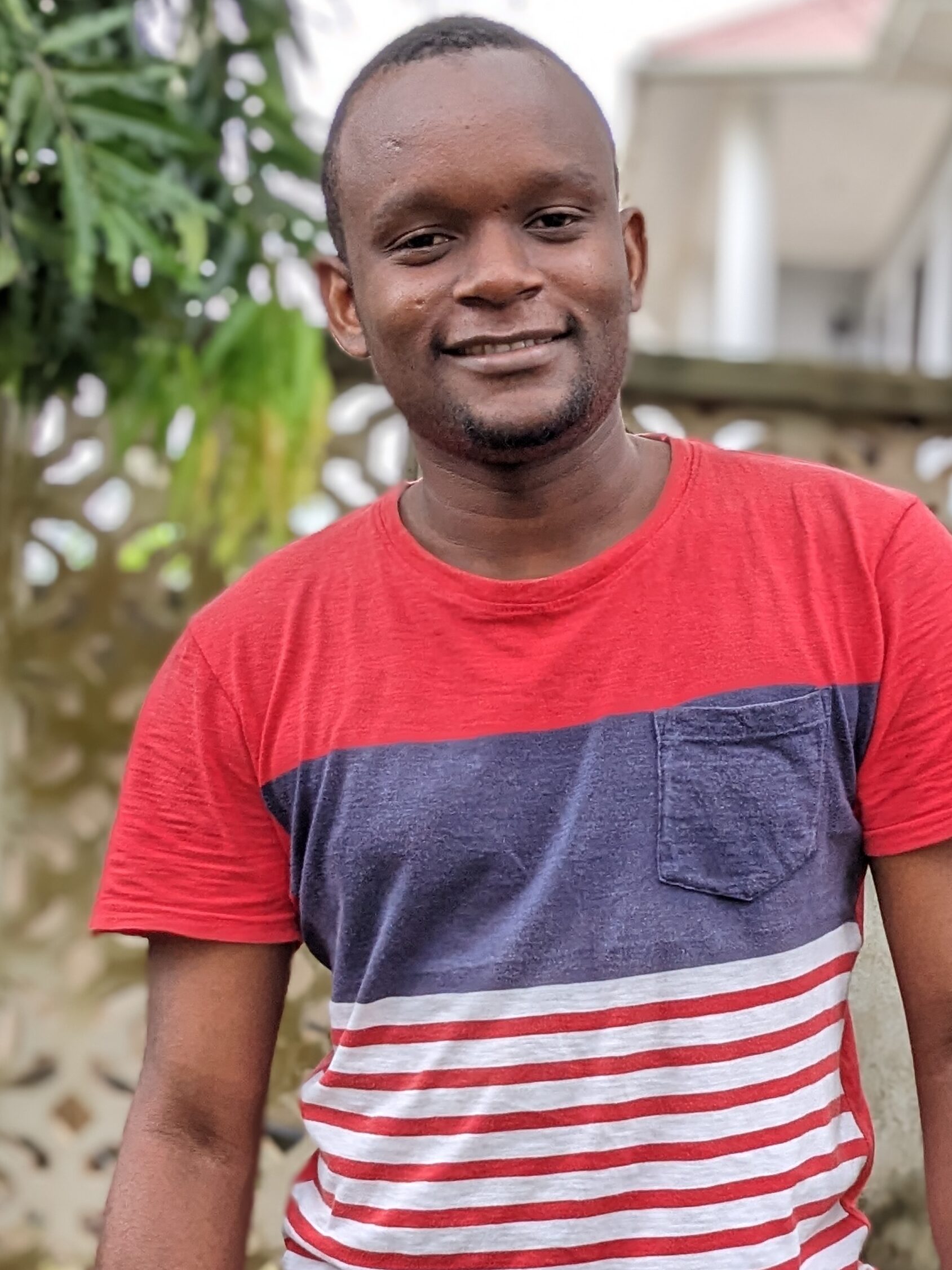

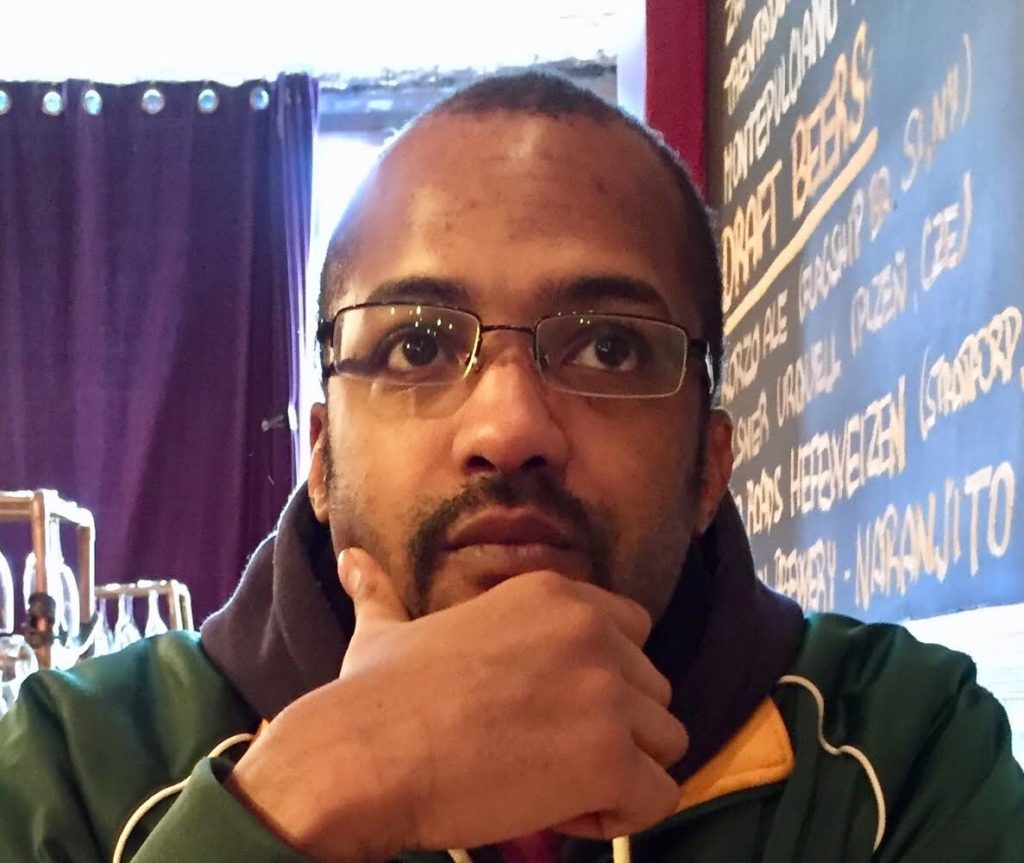

The 24-year-old black train operator was frustrated and angry. He felt a knot of tension in his chest as he contemplated stopping the train in the middle of the bridge.

He wore his faded blue uniform with a name tag that had seen better days, and his fists clenched and unclenched as he struggled between his desire to end his shift and his responsibility for the passengers on board.

As his frustration grew, he began to reduce the speed of the train as it approached the Dona Ana Bridge which caused the train’s familiar hum to transform into a rhythmic chug.

“You are making the correct decision,” he told himself as he presently pulled the emergency brakes, sending the sound of steel against steel reverberating through the air.

This caused the train to shudder and come to a complete halt, making the passengers jolt forward in their seats.

Outside, the sky displayed a blend of pale blue and soft gray clouds, hinting at the changing season.

The train operator looked at the communication device as a gentle breeze blew through the control room windows.

He then looked at the early spring sky before returning his gaze on the communication device.

Just tell the passengers the truth of what’s happening, thought the train operator as he gazed towards the communication device, If they hate you for it, so be it!

With a deep breath and slightly trembling hands, the train operator picked up the communication device.

He then cleared his throat and spoke, his voice carrying a mixture of frustration and determination.

“Ladies and gentlemen, I want to apologize for the unexpected stop,” he said, and then paused momentarily, “my shift has come to an end, and according to the system, I’m now considered a passenger rather than the operator. This means I can’t continue driving the train.”

He then left the control room and walked down the narrow aisle of the train car.

Eyes followed him, stealing glances that conveyed worry and disgust at what they saw as unprofessionalism.

His uniform, once a symbol of authority, now seemed out of place as he settled into an empty seat in the cabin.

The worn seat cushion felt unfamiliar beneath him, a stark reminder that he was no longer in command.

As he took his place among the passengers, their reactions were a blend of astonishment, concern, and even a touch of disbelief.

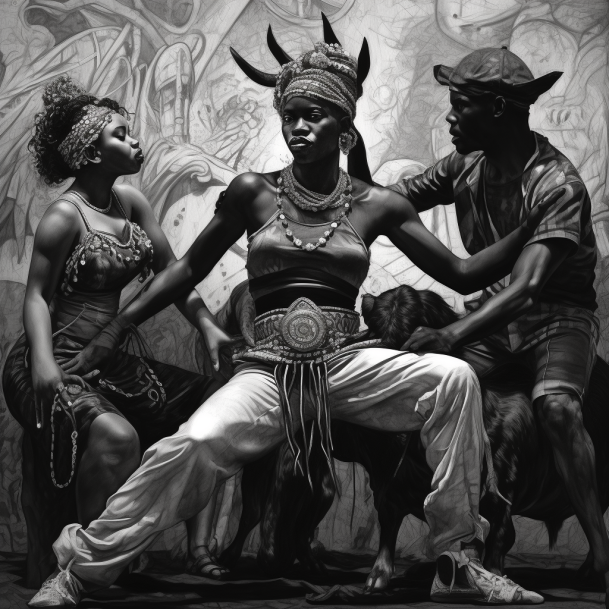

Two passengers decided to confront the train operator while the other passengers in the train cabin paid rapt attention.

“Why did you stop the train in the middle of the bridge?” the first passenger asked, fear etched on his face.

“Because my shift is over,” said the calm train operator after he let out a sigh.

“What’s the true reason you stopped?” asked the second passenger who stood in front of him.

The train operator then looked at them and shook his head from side to side.

“Stop interrogating him,” said another passenger as he pushed the two passengers away from the train operator, “help will come soon, and he will be punished!”

The train operator then grinned, placed his head on the headrest of his seat and closed his eyes. The cabin was tense as conversations among passengers centered on the operator’s lack of professionalism and empathy.

***

A few minutes later, the train operator was awakened by the sound of the communication device in the control room.

He closed his eyes as he saw other passengers looking at him and urging him to go and pick up the call in the control room.

After a few seconds, the sound from the control room ended and the train operator let out a huge sigh.

Suddenly, a protrusion from his smart necklace sprang and fixed itself on his earlobe.

“The train control center is calling you,” blurted a speaker on the protrusion.

A heavy tension settled over the train operator, like an unwelcome guest at a long-awaited celebration, as he heard the words from the speaker.

He then activated his smart necklace by slightly taking out his tongue, causing a protrusion to spring out of the necklace device and fix itself in front of his mouth.

“Pick up call,” he silently dictated as a bead of sweat formed on his forehead despite the cool early spring air.

“Hello, this is the operator in the control center speaking,” said the official.

“Yes, this is Ngweya speaking,” replied a tense Ngweya.

“Why did you stop the train in the middle of the bridge?” asked the official.

Ngweya was quiet for a few seconds and then he replied, “Because my shift is over.”

“Ngweya, please be honest, you know lives are in danger, right?” persisted the Official.

“There’s no other reason sir,” Ngweya suddenly had a dry throat as he wondered why the official said the passengers were in danger.

“Ngweya, if you have any problem, just tell us.” the Official said.

Ngweya’s mind flashed back to the times they didn’t listen to him in the past. He then said, “I have no problem!”

“Are you ready to be responsible for the lives that will be lost if you don’t move the train?” asked another official.

Ngweya’s heart quickened its pace, and his fingers nervously tapped against his thigh when he heard that lives might be lost.

He thought about what they said for a few seconds and when he could not understand their reasoning, he decided to ignore their words.

“I am just a clog in the system,” said Ngweya as he reminisced the past, “if lives are lost, the system will be to blame!”

“The bridge will collapse if you don’t move the train,” as the Official spoke, Ngweya remembered that he had heard about the infrastructure needing repair, “and we can’t come and open the control room since the AI recognizes you as the driver.”

Ngweya then tried to compose himself and rationalize his behavior to allow him to have a good conscience even if the bridge collapsed.

“You know we can’t force you to open the control room since it’s against the law,” continued the official, “so all we can do is ask you to move the train and tell us your complaints.”

“My shift is over,” said Ngweya after digesting the information about the bridge’s possible collapse, “I am ready to die to follow the system!”

He then silently dictated, “Cut the call.”

Ngweya’s tension escalated to near-breaking point after his conversation with the train control center.

Their words reverberated in his mind like a warning siren, echoing with the realization that the bridge wasn’t designed to support the train’s weight for an extended period.

Yet despite the urgency, and the potential danger to both the passengers and him, the operator remained resolute in his decision not to move the train forward.

After a few minutes, a discernible panic swept through the passengers as they learned about the potential bridge collapse.

Concerned for their safety, a group of passengers then took decisive action and attempted to bully the train operator to continue with their journey.

“Open the control room and at least move us across the bridge!” shouted one passenger as he grabbed the train operator’s collar.

“Or open the doors of the train so we can walk to safety!” he shook the operator as he said this.

Ngweya shook his head left and right as he looked at the concerned passengers with a stoic facial expression.

Another passenger then broke the tussle between Ngweya and the concerned passenger.

“Let him go, help will come soon!” said the passenger as he tried to obstruct the aggressive attempts.

Ngweya arranged his collar and sat back down.

The passengers in the train car were now divided between those who sought to force the train operator to move the train and those who believed in respecting the dignity of the train operator and the law of the society.

After 15 minutes, the bridge’s structural integrity started deteriorating and cracks began to snake their way across the bridge.

Passengers who had previously been engaged in conversations or gazing out of windows now found their attention riveted by the alarming developments unfolding before them.

***

After about 10 minutes, a protrusion sprang from Ngweya’s smart necklace and fixated itself on his earlobe, and said, “The train control center is calling you.”

| The cracks can be seen from the windows and hence the passengers who saw them through gazing out of the windows caused the panic. Cracks can be seen through the window as the bridge is wider than the train |

He then activated his smart necklace by slightly taking out his tongue and causing a protrusion to appear in front of his mouth and then he lip synced, “Pick up call.”

“Ngweya,” said the Official, “we have abandoned the idea of saving the train, we are now trying to ensure the land below is as soft a landing as we can create.”

Ngweya stood up then and went to peek through the window and saw fractures in the bridge’s structure.

“You are the only one who can help us now,” continued the official.

Ngweya returned to his seat and after taking a big breath, he lip-synced, “I am only a passenger now, my shift as a train operator is over.”

“C’mon Ngweya!” shouted the Official, “You are human! Break the rules to save lives!”

“I tried to whisper to the system, but they didn’t listen and now you will be forced to hear my screams,” said Ngweya sternly.

“What does that mean?” cried the confused official. “this is not the time or place to hold grudges, Ngweya!”

“This generation is too soft and fragile,” said a voice in the background as the official continued trying to convince Ngweya to change his decision, “now he is going to be the reason for so many deaths!”

The words infuriated Ngweya and he then softly said, “The designers of the system should be more careful next time!”

“You know that if you survive, people in the government will vote for you to be heavily punished!” the official tried a last attempt at fear mongering to change Ngweya’s mind.

“I am ready to die for the system!” said a confident Ngweya.

Before the officials could speak any other word, he silently dictated, “Cut the call.”

As the minutes went by, the cracks on the bridges surface became bigger, which caused the tension among the passenger to reach a fever pitch. In a bid for escape, some passengers attempted to break the windows, which had steel bars on them, while others attempted to stop them, fearing the commotion might hasten the deterioration of the bridge.

Amidst this tumultuous scene, the once-angry and troubled train operator sat hunched over, his demeanour now a mixture of helplessness and resignation.

As the chaos inside him conquered his mind, a protrusion from the smart necklace sprang once again to his earlobe.

The action startled him and caused him to sit upright. The speaker then said, “Mwanaidi is calling you.”

He felt a tense pain in his heart as he realised that the officials must have told Mwanaidi about the situation and she would try and change his mind.

He activated his smart necklace and picked the call.

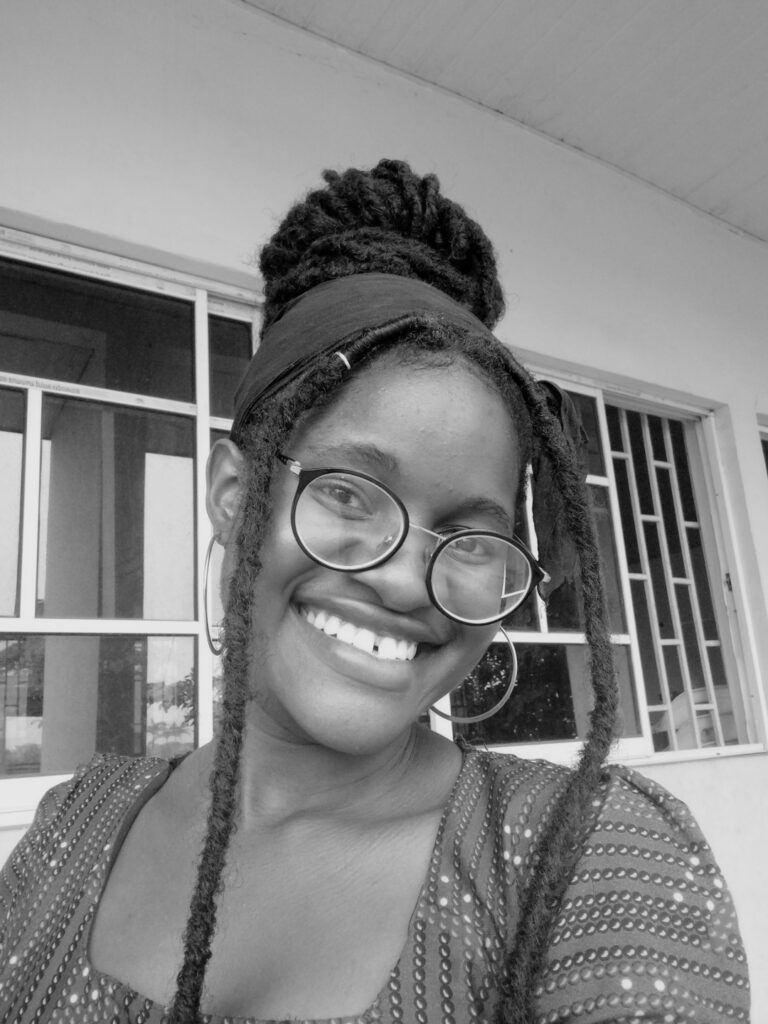

“Hi, brother,” said Mwanaidi.

Ngweya hesitated for a few seconds and then answered, “Hi.”

“Why did you stop the train?” asked Mwanaidi.

“My shift is over.” answered Ngweya with an assertive voice.

“Yes, but there must be a reason behind it,” continued Mwanaidi in an innocent tone.

“There’s none, little sister,” said a calm Ngweya as the chaos in the cabin filled his ears.

After a moment of silence Mwanaidi asked, “Is it because of what happened to mom?”

Memories of his mom then flooded his mind as he momentarily became deaf to the noise in the train cabin.

“I know that you usually don’t change your decisions easily,” Mwanaidi began in a soft tone. “So, please tell me your requirement so they can do it and help avert the catastrophe.”

Ngweya didn’t answer but just breathed heavily causing Mwanaidi to think that she was making headway.

“Is it the rules?” asked Mwanaidi and then paused, “I know how it felt when the rules caused mom’s death.”

“Not really,” Ngweya started sobbing as memories of the funeral of their mom started flooding his mind.

“It hurts me too!” Mwanaidi spoke through tears, “they changed the rules but it was too late!”

“Stop, Mwanaidi” cried Ngweya as the emotions were just too much for him.

“Let’s not cause the pain we are feeling right now to so many other people,” Mwanaidi mumbled, “please tell me how they can make it right so you can move the train.”

Mwanaidi then kept quiet for a few minutes to let Ngweya know that she was ready to give him as much time as it would take for him to say why he stopped the train.

“So,” said a sad Ngweya after composing himself, “I was fined for being late to the job in the morning.”

“Mmm,” replied Mwanaidi softly.

“Even though it was because the automated transportation system was late to bring the pod to my place. I told them it wasn’t my fault,” continued an angry Ngweya, “but they didn’t listen, and I also found the train parked 20 yards from the station.”

“Yes, go on.”

“I asked them why it was parked there,” Ngweya’s voice rose as he spoke, “and they said the person’s shift ended while he was there.”

“Mom died because the doctors’ shifts had ended and those who were on shift hadn’t arrived,” Ngweya continued, after pausing for a few seconds.

“Yes, and we fought in the direct democratic government until the law was changed,” said a proud Mwanaidi.

“Yes,” continued Ngweya and then paused, “but they didn’t accept to change the law that allows people to leave their workplace when the shift is up for every institution.”

“Yes,” said Mwanaidi, beginning to understand her brother’s frustrations.

“I proposed the bill to do that but they voted against it,” continued Ngweya as he looked at the chaos inside the train cabin, “so today, I am going to show them that the law needs to apply for all institutions.”

Mwanaidi then kept quiet as she tried to process what her brother just said.

“They ignored my gentle nudges,” continued a furious Ngweya, “now they will have to notice my forceful expressions!”

“Okay, they have heard your side of the story and they said they will change the rules,” said Mwanaidi after a long silence.

“No,” said an emotional Ngweya while shaking his head, “I am not changing my mind, let this be a lesson for all generations to come!”

“Ngweya,” mumbled Mwanaidi after a few seconds of silence, “you are the only family I have!”

Ngweya then closed his eyes as his sister’s words caused a surge of worry through his body.

“Don’t leave me,” continued a crying Mwanaidi.

Ngweya could only muster a sigh as he recalled how he had promised to take care of her when their mom died.

“I swear,” mumbled Mwanaidi as she rubbed tears from her eyes, “If you die on that train-”

“Don’t,” interrupted Ngweya.

“I am going to follow you and mom wherever you are!” uttered a sobbing Mwanaidi.

“Don’t say that,” Ngweya was now crying.

“Then, please,” said Mwanaidi as she composed herself, “just tell them what you want so this can be over!”

“Okay,” said Ngweya as he also composed himself, “I want the rules in the transportation institution to be changed to allow people to overstay their shifts for the sake of humanity.”

“Okay,” replied Mwanaidi softly after a few seconds, “let us work on it.”

Ngweya then looked at the ceiling of the train and let out a shout as the tension inside the train cabin continued intensifying to a nearly unbearable level.

He then observed the passengers as thoughts consumed his mind.

Will they really change the rules? thought an anxious Ngweya as he closed his eyes and rubbed his face. And what if they don’t? Should I really let these people die? Should I really let Mwanaidi die?

After a few minutes, a protrusion sprang from Ngweya’s smart necklace and fix itself in his earlobe. It then uttered, “There’s a bill that has been proposed in the transportation institution.”

Ngweya then took out his scrollable tablet which was no bigger than a pen—from its slot in the smart necklace and then un-scrolled it.

He activated his smart necklace and silently dictated, “Open the transportation institution app.”

He then read the bill and voted for it.

***

As Ngweya continued contemplating the bill and the results, the structural integrity of the bridge continued to deteriorate rapidly, with widening cracks spreading like jagged veins along its surface.

The once-sturdy support beams groaned under the strain, and the entire structure seemed to begin a perilous sway.

Inside the train’s cabins, panic had given way to a primal survival instinct. Passengers clung to anything stable, each person filled with fear and desperation.

Ngweya felt the tension in his heart and stomach threatening to reach a breaking point as he waited for the bill results while trying unsuccessfully to ignore the chaos that was going on inside the train cabin.

He then went to look outside the window to see if there were more signs of damage on the bridge.

“Ahhh,” blurted Ngweya as he saw the signs of the bridge collapse. A melancholy enveloped him after seeing the gravity of the situation.

He then returned to his seat and gave the control room door the 1000-yard stare.

Should I just move the train? contemplated Ngweya as it finally dawned on him that their chances of survival were diminishing with every passing moment.

The results are a few minutes away, reasoned Ngweya, let’s hope, the bridge is able to stay intact for a bit longer.

Ngweya then activated his smart necklace and silently dictated, “Please generate a sad song for a person who is faced with a hard decision between saving a few lives in the present or saving many more lives who will live in the future.”

After a few seconds two protrusions from his smart necklace fixed themselves on both his earlobes and a song started playing in his ears.

He then buried his head inside his thighs, closed his eyes and listened to the song which repeated after it ended.

After about 12 minutes, the song stopped playing and the speakers in the protrusion device blurted, “The bill results are ready!”

Ngweya felt a surge of electricity pass through his body as he knew the results would determine the fate of all who were currently in the train.

He then activated his smart necklace and silently dictated, “what are the results?”, and then clenched his jaw and grimaced.

The speaker on the protrusion fixated on his earlobe then blurted, “The bill passed!”

Ngweya took in a deep breath and let out a sigh of relief. He then stood up and looked at the chaotic environment in the train cabin.

He then started walking towards the control room. A wave of relief and happiness swept through the passengers as they witnessed Ngweya make his way back to the control room.

Once inside, he shut the door and turned on the engines and they roared to life.

Unfortunately, as Ngweya began to move the train, the bridge, which was already weakened by the strain it had endured, began to crumble under the weight of the train.

Sections of the structure, behind the train gave way, sending debris plummeting into the abyss below, and causing the ground to tremble.

Ngweya continued to inch the train forward hoping to escape the impending disaster.

Maybe it’s too late, Ngweya grimaced as he continued to drive the train forward.

As the train moved, the gap between it and the collapsing bridge narrowed, causing most of the passengers and even Ngweya to brace for the worst.

But in an awe-inspiring display of precision and timing, the train just managed to clear the crumbling Dona Ana bridge.

The train cabins were then filled with gasps, roars and shouts as the sensation of relief and disbelief washed over the passengers.

“Thanks mom,” thought Ngweya after they managed to get off the bridge onto regular tracks on land.

Ngweya then continued the journey and tried to keep his mind away from the traumatic events that had happened in the last couple of hours.

After a few minutes, Mwanaidi called him again.

“Hey brother,” said Mwanaidi.

“Hi,” said a timid Ngweya.

“I understand what you did,” continued Mwanaidi.

Ngweya then chuckled and said, “thank you!”

“But you know that you might be in a lot of trouble?” asked a concerned Mwanaidi.

“No,” said Ngweya confidently and then paused, “they can’t punish me for following the rules!”

“Ah, whatever happens, I love you!” softly spoke Mwanaidi.

“I love you too!” replied Ngweya.

A silence then took over the call and after a few seconds, Mwanaidi blurted, “I want to hear the story of what happened in the train!”

The words caused Ngweya to chuckle as memories of the day flooded his mind. “I will call you so we can meet when I arrive there,” Ngweyasaid before he hung up.

As the train continued on its journey, Ngweya’s mind was a whirlwind of emotions as he rationalized his actions by thinking of all the lives he had saved by making the law pass.

THE END!