(A Sauúti Story)

Mi’iqoa woke up and forced himself out into the cool, early morning air; the low red sun lit up the ever-present, sheltering rock face of Rez’dhauh a short distance off. She was always a blessing to behold, no matter how much kalabash wine had been consumed the night before.

It seemed an age since the excitement and fervour surrounding the adulthood initiation ceremony of him and his other age-mates had occupied their every moment. The past few juzu had dragged along, with his sister’s group two juzu before him showing the promise and wonder of their newly anointed lives, while his destiny seemed forever out of reach. And, as if suddenly, his was only a moon cycle away, then a sleepless night before, and finally it had culminated two bés ago in the closing ceremonial procession winding its way up the blood-red mountainside to the near-flat summit.

Despite the magic in the air; despite the joy and songs shared, there had been nothing auspicious, no monumental transcendent visions, or meaningful dreams.

Since the last moon cycle, his body was heavy. He was more fatigued than usual; a weariness unlike the foggy head after late nights and fireside nonsense. He was tired.

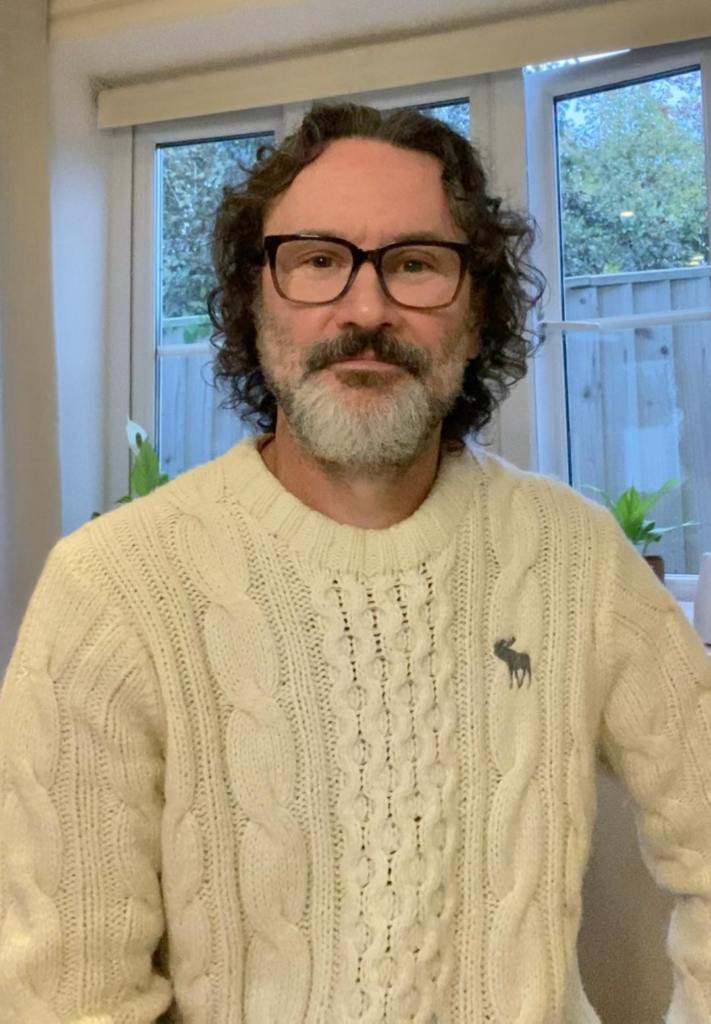

Mi’iqoa rubbed his face and scratched his matted, dreadlocked scalp. He huffed at the thought of having to traipse up there now, but the idea of draining the entire mountain’s worth of water to quench his thirst compelled him forward. Making his way through the short grass, the dew wetting his bare feet and ankles, the familiar mi-i-tok chirping click of the beetles, of his namesake, filled the early morning air. Disturbed by his footfalls, one of the dark blue insects sprang away to his right and continued its dawn call.

Rising above low, ash-grey shale slopes, stood the majestic stretch of ruddy volcanic rock that was Rez’dhauh. At the height of a dozen mighty ngõgda trees, dawn and dusk set her red, purple, and brown granite aflame. But this burnt mountain of the dry region held within her impenetrable surface both a sweet, cool sustenance, and the primary means of subsistence for those living in her foothills.

Weathered by time, a circular pit had been etched deep down into her, opening an ancient underground water-source of unknown origins, in a land devoid of regular rainfall.

On rare occasions, without warning, the waters were known to bubble and geyser high into the bright blue sky. Neither tremor nor rockfall could be observed, just the inexplicable tumult bursting from the usually tranquil and cool well.

Mi’iqoa strolled over the loose coal-like shale up to the base of the mountain. Passing alongside the large, oval basin built at waist height and connected to the rising rock, he climbed the short wooden steps onto the main ledge.

He took a moment to look back over the village spread out below. Though quiet, smoke drifted up from many of the low hide and wood huts of his people dotted around the flat grassy plain. The morning air was warming; the sign the second more radiant and fierce sun was on her way to the horizon, and his cue to begin his climb. By the time both suns were vertical, his people would be willing the twin suns to dip behind the sacred mountain, for Rez’dhauh to stretch her cooling shadow over them for some reprieve in these scorched lands.

Level with the ledge, the rock and mud basin, sealed by a fixed wooden cover, stood empty. Any last drops of water it still held would be dried up by midday. And so, his reason for being here: his turn at the well to replenish the trough for the villagers. For soon, the early rising elders would make their way to the water basin, and another reason he would have to hurry. He couldn’t imagine getting old. He hadn’t thought that far, hadn’t even figured out what he was doing with his life day to day.

Looking from the basin to the wide inlet, he stepped into the shallow channel and began his steady ascent.

Many a juzu had passed for this well-worn, zigzagging walkway to be carved by his people’s bare feet treading up and down the mountainside; and smoothed by the rich well waters flowing down to fill the ancient tough.

In a time before anyone could remember, the ancients had climbed up this red rock to get to its waters, instead of labouring down a precarious mountainside with weighty kalabash buckets, forming a narrow channel. The pathway became the waterway. And like the well itself, it became part of the mountain, part of the ceremony, and part of their world, flowing freely into the constructed trough below. And the ancients and their descendants had never attempted to tap into the side of the hillside rock to get to the water more easily because of the Echo Well’s sacred nature, as a source of resonant magic.

Though venerated for generations of Mi’iqoa’s people for her life-giving waters, it was her magic which was soon to be revealed to this young and weary villager, and the reason his people would go on to hold her more sacred than ever.

The morning sunlight warmed his sides as he climbed, left, then right, then left, on and on, higher and higher.

The summit was always a welcome respite. A time to sit, for a moment’s rest, and a time to enjoy the magnificent view of the world all around him, from horizon to horizon. Weather-beaten and smoothed, the undulating surface of the mountaintop curved and rolled away in all directions.

He stood back up, noticing his dull headache had abated, and made his way along the remaining portion of the channel to a wide, curved, almost bowl-like niche in the rock with the black maw of the well in its centre. His people believed it had been carved out by the elements, the wind whipping around the mountain and grinding away, with loose rocks and stones, over thousands of juzu. They had constructed a wooden barrier to encircle the well for safety, and enabling a bowed platform to be erected across it.

Two saplings had been bent from either end and tied together in the centre with a pulley system attached. A large kalabash container, tied to thick kalabash ropes, was lowered through a circular gap cut out the middle of the walkway. Quick, brisk pulls on the rope got the receptacle to the waters far out of sight, in the depths of the mountain herself. Heavy-laden, and depending on the level of the waters granted by Rez’dhauh, countless slower tugs would eventually bring the kalabash bucket into view. Once up through the gap in the platform, the dangling bucket was angled over the curved wooden gutter attached from the platform down into the beginning of the channel to flow down the mountainside.

But, before any of these practical duties would happen in the ritual, the waterbearer, today Mi’iqoa, must lie face down on the sturdy platform and gaze through the opening into the cool, dark abyss below.

The sweet, refreshing scent of the subterranean waters was enough to entice him to trust the craftsmanship, and move beyond his fears onto the platform, as he had been doing for the past two bés.

He would then recite the gratitude rite, the magical poem compiled by the ancients that asked Rez’dhauh to raise her sacred, life-giving waters and echo back any teachings or infuse the waters with her healing minerals or, possibly, visions.

The old wood creaked as he stepped tentatively onto the walkway. He held one of the bent saplings, more for comfort than any needed balance. Before taking the last two steps to the centre, he went down on his haunches and crawled over, his gaze fixed on the opening and the rope disappearing downward. His throat was suddenly dry. Anticipation or thirst, he gulped and rested on his chest, chin at the edge, and gripped the wood. Mi’iqoa wondered what it would be like to roll over the edge and disappear into the cold darkness. Did it have a bottom? Would he reach Eh’wauizo?

Over time, various words and magic uttered into the well, had the remarkable effect of them coming back, echoed louder, but reversed and distorted, in the speaker’s own voice. As with the practice of speaking with an elder or the village healer, hearing your own worries and questions repeated back to you allowed for inner reflection. But the well was far more magical. Tidings, foresights or lessons could be discerned from those strange vibrations rising into the clear blue skies.

Mi’iqoa ran through the phrases in his mind, allowing their rhythm, their beat, to calm his racing heart.

Almost immediately after reciting the words, the sound of the waters rumbled, too far below in the darkness to see, churning and rising enough for the waterbearer to lower the bucket and retrieve as many kalabash loads as possible before Rez’dhauh withdrew her offering back into her depths.

He rolled onto his side and glanced around, the second sun warming his face and body, then whispered, “Dear Rez’dhauh, please, can you bring the water up even a fraction more than you did yesterday? Thanks.” He then added, “It’s Mi’iqoa, by the way.” Regret immediately knotted his stomach as he wondered if the mountain would hear his sarcasm. A gust of wind whistled around him, creaking the structure holding him suspended over the void.

Apart from the physical exertion and the honour, or burden as Mi’iqoa viewed it, was how salty or sweet, how revitalising or intoxicating, the day’s water infusion would taste to the villagers by Rez’dhauh, according to the quality of the waterbearer’s own magical pronouncements. Though some spoke of the possibility of poisoning and death, and hence the careful selection of those deemed worthy enough to recite and retrieve water on the peoples’ behalf, this had never come to pass.

There Mi’iqoa lay, pondering his life, wondering why the elders had even chosen him as worthy to perform the duty.

He turned back onto his stomach, took a deep breath, and paused. The words were difficult to speak, though he knew them by heart. With his people relying on this morning’s task being completed, he forced himself to focus on the words, but others muddled in and moved about in his mind. He breathed out and in, and recited the words.

Echo Well, sing back to me.

Sing back to me, Echo Well.

I breathe into you,

You breathe out to me.

Muscle and skin tingled as the magic permeated his weary body. Faint and barely discernible, his voice was echoing back. I breathe out to you…

Loosening his jaw and unclenching his teeth, he relaxed his grip on the wood, raised his voice, and quickened his speech.

We whisper, you speak.

We speak, you shriek.

We cry, you bawl.

We bay, you bellow.

We chatter, you clamour.

We scream, you roar!

Slam! His hand slapped the wooden walkway, sending reverberations downward. –You roar!– repeated the final echo of his voice, but strange, followed by a buffeting cool wind. Though they were someone else’s words of old, there was always meaning in the echoes, he thought, and continued the rite.

We give you our lives,

Our burdens, our woes.

Our pity, our pain,

Our loss, our strain.

Your benevolent blessings

Our bountiful gain.

–You pity your woes. See blessings in pain. I give you life. Give yourself life.–

Mi’iqoa hesitated for a moment, absorbing what came back, wondering who else had heard the same, echoed repeatedly over time. He uttered the final phrases.

We ache, you comfort.

We bleed, you seed.

We receive what you offer,

No more than we need.

The air pushed upward before he heard the distinctive sound of a rising storm. Standing, relieved and rejuvenated, he took his place at the kalabash rope and pulley, and began hurriedly lowering it. Further and further it went, rattling and squeaking with every vigorous tug.

The rush of the rising water quieted, yet the container had not hit the surface. Suddenly the rope slackened and up came the splash of the bucket. To Mi’iqoa’s frustration, Rez’dhauh had obviously pushed her water level up less than the bés before. He resigned himself to his arduous task, setting his jaw tight and yanking at the taut rope.

The suns were blazing, and Mi’iqoa had lost count after a dozen or more loads pulled up and splashed down into the gutter to the channel. He was tired and his arms and shoulders ached. The elated hum of the villagers far below signalled the water was reaching its destination.

A flock of small birds had gathered along the channel a few paces from the well, chirping and chatting, bathing and drinking their fill of the cool water colouring the rock a deep, rich red.

“Last one,” he said to no one in particular, or maybe the birds. But rather than tipping the entire kalabash out, he kept a portion, his first portion for the day, as his reward. He was still panting, sweat stinging his eyes, as he plonked the container on the edge of the walkway and slumped down, dangling his feet over the gaping well.

“Let’s see how it tastes.” As on his previous shifts, he had waited until the task was complete before he sampled any water from his batch. Tongue sticking dryly to the roof of his mouth, he lifted the bucket to his lips and gulped as much as he could before needing a breath.

He shrugged. Not as sweet as he had hoped, but it was refreshing enough after the hard work. He drank his fill and, with a final tip, splashed himself from head to toe with what remained.

His skin tingled with the coolness, and his body relaxed into a burning ache. Slouched over, he watched the water droplets glisten and fall away below, quickly disappearing.

He gave the bucket a shove, teetering it over the hole in the walkway and falling over to dangle by its rope, ready for tomorrow.

Mi’iqoa should have felt uplifted, having delivered the essential water to his people. Instead, he was relieved that he was done for the day. The heaviness returned and, exasperated; he swung his weary legs limply onto the walkway, lay face down at the bucket hole, and sobbed.

Salty tears burned his eyes and dripped off his nose, and like the water before, sparkled and disappeared. With an aching, choking throat, he caught the sobs between quivering breaths. The sound of a distant plop came up to him.

“What’s next? What am I supposed to do with my life? Everyone seems to have found their purpose, their duties as parent, artisan, hunter. What am I? A repeater of the words of others?”

He could not imagine living the rest of his life like this.

“What am I?” he gritted his teeth.

“I am scared.” He spoke the words that had been on the tip of his tongue, the words that demanded to be spoken. He shook his head.

Finally, all he could do was speak.

“I am tired. I am weak. I am lacking. I am scared!” The words moved, unrestricted, louder. ”I am unsure. I am inadequate. I am incomplete. I am unheard!”

A rhythm came, moving through him like a steady drumbeat, echoed by the thump of his hands.

“My life was muddied, my way unclear. My days, my dreams, were driven by fear. You filtered my mind, my thoughts distilled. Your waters refined; your magic filled. You drip, you trickle, you flow, you flood. My waters are clear, no longer mud. My path was stifled, rutted, and grooved. My channel’s now open, flowing and smoothed.

“All I can give the world is my truth. All I can offer are the worries of youth.

“I want to shout. I want to cry. Squash my doubt. I want to fly.”

At first, his words came back unchanged, echoed and amplified, yet laced with the familiar magic and promise.

Just as the sounds subsided, and Mi’iqoa caught his breath, there came an upsurge of wind, and the walkway quivered.

The flock of birds took flight, quickly vanishing into the blue sky above him.

The surrounding air sizzled with sparks of light, the sound like a rushing roar filled the well. Just in time he looked over the edge of the walkway to see the water barrelling up in a shimmering, turquoise, glassy mass.

Mi’iqoa leaped off the platform as it flooded over the wooden structure. But rather than blasting out like the geysers of legend, it flowed in gentle pulses, staining the rocky surface a shimmering crimson in the sunlight. He chased the flow and stopped at the edge of the mountaintop. The wide wave flooded uncontrolled down the steep slope, but eventually narrowed and channelled into the drainage path and into the basin.

Louder than the falling waters, the shouts of surprise and joy from those gathering around their water source carried up on a cool gust of wind.

The words continued to run through Mi’iqoa’s mind, coming out in the same steady beat. Rhythm, poetry and song; he could feel it in him.

Our words, our songs, are your victual to receive,

Your waters, your echoes, are our reprieve.

We must not withhold; we must not let brew.

We take our truths, and speak them to you.

Your patience unyielding.

Your waters unending.

Mi’iqoa gave us new words to say. And Mi’iqoa allowed us to use our own words, our own truths, spoken out into our world.

#