I cannot really say why I did it. Perhaps I have been around for too long. And these days, I have very little to do. Serves me right I suppose. I’ve been around long enough to know not to interfere with the world of men. They’re all so capricious. Fragile things. But it was such a small thing. And this, what we do, gets so repetitive. But there was no malice in my intent. If anything, I was trying to help. Not for any benevolent reasons as that word, help, usually presupposes. I don’t know, I guess after all this time, the urge to participate got the better of me.

***

I knew all of them. I knew them as well as I’ve known any other human. They passed by often on their way to and from school. They came to play in the afternoons while they were herding their cattle. They would throw their dirty, threadbare clothes on the gleaming rocks and their naked bodies would leap into the air. I liked to take a moment then to look at them, their utterly blithe indifference to the plights of life, limps splayed out wildly, the backdrop of a clear blue sky framing their frail silhouettes. Then they would come down, landing in the cold water with grimaces that seamlessly transformed into laughter. I would feel them. Touch them. Caress their scarred skins and listen to their hearts beat against the infinite symphony of the river. I would cling almost tenderly to them and marvel at the impudence of their youth.

This world does not have a name for me. Only a ritual. Chenura in this part of the world. An acquittal ceremony for the souls of the deceased. It is less common nowadays ever since that Jesu decided to take on a physical form and walk among men. And then they went on to write about him in that book. Oral tradition cannot compete with a book. Nowadays, very few people make the request to their children that they want the Chenura ritual to be done after they die. And even when they do, some of the children refuse, citing conversion to their newfound faith, the one that Jesu started. Nowadays there is only the funeral and then the Nyaradzo, the remembrance. It used to be that sending someone forth; to the realm beyond, to elevate them to the status of mudzimu, was requisitely paramount. Joining one’s ancestors was the highest form of transcendence. Now they call the ritual heathen. Dark. Unclean. I have to give it to him, Jesu was clever. But just as well. Maybe once I’m no longer needed, I can, to use a human term, retire. I will join the others that have been denounced.

I like the water. I like rivers to be specific. I like to listen to them and to watch them. I am intrigued by their continuous state of perpetual transformation. Always changing, never the same. Whether they are a trickle during the heart of the dry season, parched and emaciated and reduced almost to a whisper, or full and violent after the rains, roaring their might and making the banks quake in abasement. That is why I mostly dwell in the water until I am called to do my job. I am no longer as busy as I used to be.

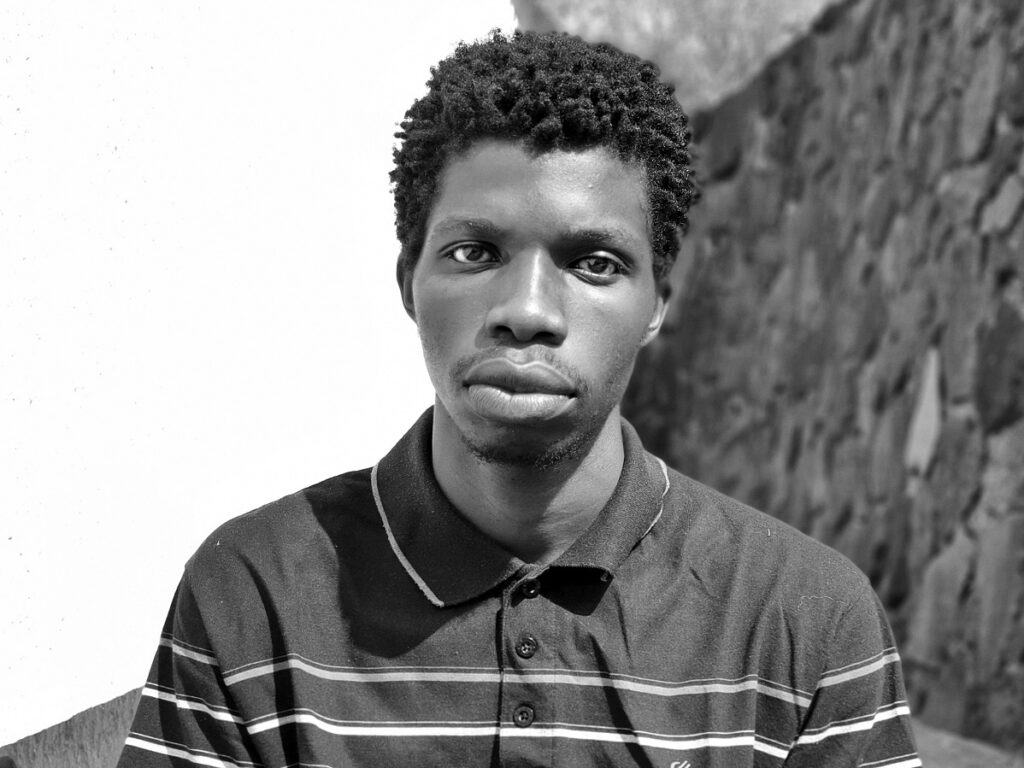

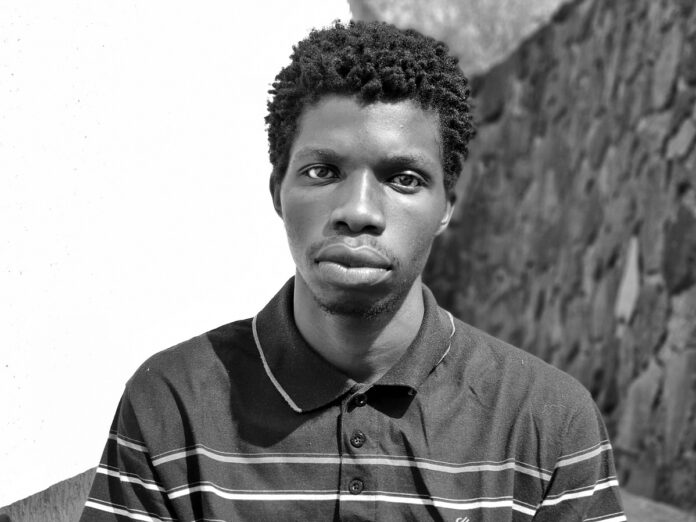

There were four of them, all boys. I learned their names as they called out to each other while they dived and splashed and swam in the waters of the Mumvumira, one of the rivers I call home. Learnmore, Kudzanai, Tawanda and Decision. I learned their histories when I ripped their spirits from this realm. Kudzanai and Decision are – were brothers. They were inseparable. The villagers, the few still left who believe the things of the old world, said that it was because they had been born only one year apart and had drunk the same milk from their mother’s breast. All four of them went to Bemba primary school, Decision in the fifth grade and the other three in the seventh even though there was a four-year gap between the oldest and youngest of them. They lived in Nezambe, an otherwise insignificant village were it not for the fact that my river is etched into its valley. I only dwell in the ones that never dry up and Mumvumira is one of them. Even when the drought of `92 came and all the streams became no more than dry, cracked, skeletal appendages, Mumvumira’s waters continued to flow from the crest of Nyamhemba.

There is a quiet spot along her course. Hauntingly serene. The villagers call it Birira. Some of them believe it is sacred. Others that it is cursed. Whatever the case, I have nothing to do with it. Mine is not to curse or bless. Over the years, I’ve discerned that the superstition surrounding it stems from the several bodies that have been found caught between the rocks that are scattered all over that particular site. Eyes rolled backwards, skin wrinkled and grey, their facial expressions cemented by death and stomachs bloated with water. Broken things. Dead things. I watch idly when their relatives and neighbours forlornly uproot their bodies from the water and I wonder what emotion must be burning a hole in their chests. Anger? Grief? Musikavanhu forbid, joy? You never know with these creatures. But whatever it is they feel as individuals, I can always detect a communal feeling lurking underneath everything else. I smell it. Fear. Acutely pungent and suffocating. As if at any moment, they too might drown like their dead neighbour or cousin or brother or mother-in-law. The body movers always do their best to be graceful, but for all their efforts at sacralisation, I have been doing this long enough to know that there is no grace in death. And they are frequently too eager to leave, too rushed and unsettled to be delicate. On normal days, very few dared to venture anywhere in the vicinity of Birira. Except stupid children. Yes, stupid, for I cannot bring myself to believe that they were brave.

It was cold that morning. A ghostly layer of mist floated ominously above the icy water. The mukute trees that lined the river bank howled against the chilly wind and the reeds frantically shook the cold dew off their leaves. The sun was still shying behind Nyamhemba. What little of its light shone through was veiled by thick grey clouds that sat malignly in the sky, relishing the view of the shadows they cast on the world below.

It was Decision’s voice that drew me. It was close. Too close. The boys often crossed the river on the makeshift footbridge that was several meters upstream. I usually went there to watch them cross over the tree trunk that had been precariously laid across the span of the river. Sometimes they crossed silently, sleep still clinging stubbornly to their swollen faces. Other mornings they called out and teased as they went along.

“Iwe mhani, give me back my pen.” He sounded distressed.

There was a brief pause and then raucous laughter. The kind whose fringes are slimy with hostility. The laughter of a bully.

“I told you what you have to do mufana. Respect your elder.” It was not unusual for Kudzanai to tease his younger brother, but that morning, something in his tone made me think of the dark clouds above as their footfalls edged closer.

“I’m going to tell on you. I’m going to tell Baba.”

“Do that and see what will happen.”

Rightly noting that his threat failed to have the desired effect, the younger boy once again resorted to pleading with his brother who had become even more incensed by the attempt to coerce him.

Kudzanai was the first to appear through the reeds that flanked the riverbank. He wore their school’s khaki uniform underneath an oversized maroon jersey that had holes at the elbows. His twiggy legs rose out of undersized brown school shoes that had been to the cobbler a few times too many. A bag of Gloria flour and a length of string liaised to form an improvised satchel and hung from his shoulder, empty save for a pen, half of which had been chewed off, a pencil cut in half, the other with the younger brother and a lunchbox containing their shared break-time meal of cornmeal bread. He planted himself on a rock and waited for his brother to catch up. In his left hand he held a white pen, the words EVERSHARP 15M printed on its side in shiny gold. He held it out over the water.

Seconds later, Decision burst through the shrubbery and nearly tumbled into the river.

No one could mistake the two for anything other than siblings. They shared the same mango coloured skin for which their friends often taunted them, calling them masope. Their hair was a dirty reddish-brown with a sickly soft and curly texture as if they had kwashiorkor. The colour matched their eyes which discoloured almost to hazel when the sun shone directly on them. The only apparent difference between them was their heights. And their noses. Kudzanai’s was flat and wide like a frog ready to prance while Decision’s was more rounded.

Learnmore and Tawanda, their faces rigid, followed immediately after. I smelt the fear on them. Tawanda, the eldest of the quartet, looked around restlessly.

“Machinda we are going to be late for school. Stop playing around.”

“I am not playing.” Kudzanai’s resoluteness resounded in his chillingly calm tone. I was intrigued. I seldom got visitors and usually when I did, the occasion was always tainted by the morbid ambience. This was new. Perhaps that’s why I did what did.

“All he needs to do is say that I am the boss and I will give him his ballpoint back. Isn’t that right mufana?”

Decision faced a dilemma. Submit to his brother, get his new pen back and go to school, getting there in time to avoid incurring the wrath of their headmaster. Or…or call his brother dog shit and spit in his face.

Like I said, stupidity, not courage.

The pen landed in the water with a plonk. It had hardly begun floating away before I heard Decision yelp and then land in the shallow end of the river on his back. His brother stood over him menacingly, daring him to challenge him. Seeing the fire in his elder brother’s eyes, Decision opted not to provoke him any further in the absence of their father who could rescue him if Kudzanai started to overpower him. He also knew their two friends would either watch or leave them and continue to school. In the end, all he managed to do to salvage his wounded pride was mutter obscenities under his breath which he refused to repeat when his brother dared him to do so.

That should have been all. That should have been the end of it. A little spit, some wet clothes, a few heated but inaudible vulgarities, some wounded pride and a lost pen. But then they came back.

It was afternoon when I saw Decision again. An endless sheet of grey watched him along with me from above. I was unsurprised that he had opted to walk alone on the way back home, understandably unwilling to travel with his aggressor while the bruises to his ego were still so raw. Fragile things. I was a little amazed though, that he had dared to come back to a place that so many dreaded, on his own.

He stood hesitantly at the edge of the water, his face a stony mask, his lower lip quivering, oblivious to my presence, my captivated observation. After some time, he began to take off his clothes. His haste conveyed his intention to leave as soon as possible.

The pen was gone. I had watched it float away. It was currently bobbing in a small puddle some ways downstream. But he had come all this way. At the very least I found his effort amusing. That was all. I did not intend for any of the things that followed to happen. So, I fashioned him a new pen.

After Jesu, a few more of us did interact with the physical realm. It was always possible, only frowned upon. But he had taken so many believers that it necessitated a few physical manifestations to even salvage what little faith was left in us. Like letting the living see their deceased loved ones. Or granting their wishes. Even those that believed that it was us, the divinities of the old world, that had granted these things chose to hide it for fear of being castigated, being labelled as charlatans of evil. Our efforts only strengthened the belief in him. I personally had never done such a thing. Not until that day. If I had, I would have known that humans cannot handle the things of our world, I would have understood why interfering was frowned upon.

Decision waded out of the water, holding my gift in his hand, oblivious of its origins. He knelt in the sand and held it up to his face. I wondered whether in some small way, he knew that what he held was sub-natural. Or if the frozen grin on his face was simply joy. If the glazed eyes with which he glared at it was gratitude.

He remained that way for two hours. Completely naked and seemingly unaffected by the cold. Even when he heard his brother shouting his name he did not flinch. I must admit that I was more curious than concerned. I rose from the water, my interest piqued, thrilled by the anticipation of something looming on the edges of eventuality.

Kudzanai appeared first, no longer in his school uniform. Learnmore and Tawanda followed on his heels. All three of them halted immediately when they saw Decision’s motionless body, now huddled over, the pen gripped tightly in his hand.

Even though Kudzanai tried his best to sound intimidating, his voice trembled ever so slightly and the worry that suffused it was apparent. “Mufana, what are you doing here? People are looking for you at home and you are playing around here. Get up!” He took a step forward and placed his hand on Decision’s shoulder.

Nothing.

“Iwe…”This time he made no attempt to veil the concern that was beginning to prickle at him. It was not for the wellbeing of his brother. He did not want his father to find out about the morning’s events. The image of his head locked between his father’s thighs and the phantom sting of his sjambok landing on his bared bottom settled in his throat, refusing to go away even when he swallowed. He grabbed Decision’s arm.

In the amount of time it would take to hold your breath, Kudzanai was on his back, an anguished scream gushing from his gaping mouth. His hands clasped the right side of his face and blood oozed freely through his fingers. Decision was sitting astride him, pinning his shoulders down with his knees. He swiftly pulled the pen out of his brother’s eye and jammed it into his throat. I was transfixed by the crazed look on his face, the madness shadowed in venomous loathing.

Learnmore and Tawanda exchanged glances. In a brief silent debate, they argued over which of them would intervene first and eventually agreed that a simultaneous approach was the preferable choice. They approached hesitantly at first but threw all caution to the wind as the pen sunk into their friend’s throat once again, reducing his cries to gurgles. They both jumped on to Decision at the same time. The trio landed in the sand and for a few minutes were a mangled mix of groans, swinging fists, scratching fingers and kicking legs.

Tawanda eventually managed to extricate himself from the scuffle, leaving the now subdued Decision pinned to the ground by the physically superior Learnmore. Panting and caressing a gash on his left cheek, he walked towards Kudzanai, each step feeling heavier as he approached his friend’s twitching body.

The sand around Kudzanai’s head spread outwardly in a halo of blood. Tawanda’s heart thundered in his ears. He bent forward slowly and pulled the pen from Kudzanai’s neck with trembling hands.

“Kudzanai.” His voice caught in his throat, only managing to come out as a laboured croak. “Kudzanai, wake up.” He placed his hand on his friend’s shoulder and shook the body gently. Its head rolled limply to the side.

Decision, who had been struggling frenziedly to free himself, stopped suddenly. He raised his head and looked over at his brother. The surge of emotion that erupted inside him was punctuated by a sudden stiffening of his face. Not a gradual shifting of expressions but a concise and abrupt absence of them. Learnmore relaxed his hold on him warily.

When he spoke, the callousness in his voice had dangerously sharp edges. “Give me back my pen.”

Tawanda’s gaze fell slowly on the pen and then traversed the space between himself and Decision. He looked once again at it. “It’s…it’s mine. It’s my pen.”

Learnmore stuttered, “Tawaz, what are you doing?”

He was only momentarily distracted, but a moment was all it took. Decision twisted under him and succeeded in knocking him onto his haunches. He threw a fistful of sand into his face before he dashed towards Tawanda.

For the few minutes during which he hastily tried to wash the sand out of his eyes, all Learnmore heard were screams and splashes. By the time he was finally able to see again, Tawanda was already holding Decision’s head down in the water. The younger boy’s struggles were steadily waning.

Learnmore scrambled to his feet and started running towards them. In his haste and partial blindness, he tripped over Kudzanai’s body.

As I said before, humans are fragile things. Something inside the boy caved then, refused to comprehend the scene around him. He just sat down. He raised his knees to his chin and wrapped his arms around his legs. And he watched the river run by.

Decision solemnised his exit with a final weak jolt of his leg.

Tawanda stood over him, triumphant.

Above us, the dark clouds watched silently.