My name is Obaro, which means forward in Urhobo. True to my name, I was always moving forward.

I walked along the University of Lagos road in Abule Oja. It was nothing serious, just a morning stroll. I loved to take these kinds of strolls, with earphones plugged in and music blotting out my thoughts. That helped me think. It was around 7am and shops were mostly closed. The Lagos speed day – where everyone was supposed to be in a hyperactive flurry, in order to attain the kind of productivity necessary to survive Nigeria’s busiest city – was a myth, in Abule Oja anyway.

I passed my favourite food shop, Shop 10. The shopkeepers were gathered outside, doing “morning devotion” – a clap and dance worship session which they used to start the day believing it ensured a good business day more than any exemplary services they could render. I huffed and shook my head. I thought to myself: Why don’t they go set up shop early and attend to workers who leave for work too early to prepare something in their homes? It annoyed me that after squandering their own opportunity with their religious and superstitious attitude, these shop-owners would turn to blame their semi-literate and near brain-dead president for how bad the economy was.

I shook my head again and turned to look thoroughly at the road before crossing. It was a one-way road, but you had to look carefully at both sides before crossing, if you did not want an Aboki okadaman to usher you into oblivion. These commercial bike-men were mostly always high. The alternative was worse. Bus drivers were not only high but also slow. At least the bikes were quick, and if they didn’t take you to your final destination, they would get you to your current one, in time. Such was the public transport system in Lagos, the ‘mega city’. Get there late or get there late.

I crossed the road and continued my walk. Along the way, an older woman was saying something to me. I took off my headphones to hear her but returned them to my ears in annoyance. It was one of those ‘Mowa stranded’ – People who claimed to have suffered some unfortunate mishap and got stranded on their journey to somewhere important. They just needed a little help to get there. Meanwhile it was a profession. Not getting somewhere important, but being stranded.

I stopped at a Mallam’s shop to buy gum. There was an old man in front of me purchasing something. Probably snuff or cigarettes or something else not good for him at his age. He was bent almost double and taking an awfully long time. I waited impatiently. Eventually he finished his transaction. As he turned after an unusually long time, I caught sight of what he was buying. It was indeed cigarettes. I hissed and, in my annoyance, said “Oga comot for road na. Dis one wey you just stand for road like mannequin. Dem dey do mannequin challenge for here?”

He turned and said, looking me dead in the eyes, “You will hend up as a mannequin.” His Yoruba accent was heavy. I saw him fully now. He was a very old Yoruba man, with tribal marks on his face. The slashes highlighted his red eyes. He must have been drinking already, this early in the day. I took all this in in a moment. I paused my music and noticed he had gone on a tirade. I didn’t understand the words he was saying but I could understand clearly from his tone that they were invectives. He was cursing me. I shivered a bit. Of course, a modern man like me shouldn’t believe in things like that. Curses are words which had no power to magically hurt you.

But I knew better. Jazz was real. By jazz I didn’t mean a brand of music considered classic. I meant real, dark magic that was used to harm people and influence events in the real world. Why, my maternal grandmother in Ughelli had been a powerful practitioner of African Traditional Religion. I still remembered the space in her wardrobe where she kept what my parents later came to call her idols. There had been a big bowl of red water in front of it. I always wondered what was in the water. Probably palm oil. I always told myself it couldn’t be blood. There had been Fanta and Coke bottles and kolanuts, Cabin biscuits and other oddities offered in sacrifice to the god(s). My parents hadn’t always considered it idolatry. Before their conversion to the modernity of Christianity, they had been ATR worshippers, both of them. That was how I knew enough not to take jazz or the old man’s curse lightly. My paternal grandfather had been a great jazzman too. He had been blind in his old age, but they had said he saw more than those with two eyes. Therefore, being from two great lineages of jazzmen, I knew enough to be afraid of curses.

I still had memories of my father cutting us with razors on our wrists and forearms under the direction of my grandma, after which he sprinkled some protective charms on the incisions. That was before my parents became Christians and turned away from those barbaric practices. But I had confirmed the potency of those charms long before they stopped. One day, I had gotten into an altercation with someone. He swung a cutlass at my head. I wasn’t in time to dodge it and had instead foolishly attempted to block it with my arm. The cutlass bounced off, to everyone’s amazement, me included. I would later call it Metal bending. It wasn’t all magical, though. I felt the pain – sharp and loud, as if I was being hit by a blunt instrument, although I later confirmed the cutlass to be as sharp as my sister’s tongue. Yet my skin wasn’t broken. I didn’t tell my parents, or grandma, – we rarely went to the village anymore anyway. I did tell one of my aunties who confirmed to me that the charms my grandma made were still as potent as anything even after two decades.

It was against this background that I felt trepidation at the old man’s curses on me to become a mannequin. And of course, everyone knew the story of Bode Thomas, the then colonial minister of the colony and protectorate of Nigeria who had been cursed by the Ooni of Ife and had barked uncontrollably and continuously to death like a dog. The Oba was later deposed and sent on exile. Wikipedia said Bode Thomas was poisoned, but we all knew better. The Ooni had cursed him for disrespecting him saying he would keep on barking like a dog for yelling at him. That very night, Bode Thomas had started barking in his home and had died shortly after. So I knew curses were real and shivered as I walked away fast from this man’s curse.

I suddenly froze, unable to move. I was stuck, by myself. The world was moving all around me, but I was stuck in my body, like a mannequin. I remembered all the stories I had heard about curses and felt a sudden breakout of sweat on my forehead. I felt a palpable fear take over me. I shook within but couldn’t move without. I called on my grandma, her gods, and my grandfather’s spirit to save me. I didn’t call on The Lord. I had seen some Christians call on the Lord and fire countless times without any fire actually showing up. But I knew and had seen my grandma’s magic work before. So, I called on her. At the same instant, I felt my body begin to transform, a brittle, plastic feeling. My arm began to change. I was becoming a mannequin truly. Then I felt something else in my blood. My grandma and father’s blood magic fighting it. The effect of the transformation continued. It took over me, although I wasn’t a mannequin yet. My transformation hadn’t been stopped but had merely been neutralised. That was the effect of neutralising jazz.

I had heard of Acid-to-water Jazz, a jazz that turned acid to water when your enemies poured it on you. I felt different but thought nothing of it. I went home, had my bath, and went for my 11 o’clock class. I was on my way back home, in front of one of those shops along University road when I saw a woman with a child tied on her back crossing the road. She was casually, unconcernedly crossing the one-way road. An okada was speeding down from the other side. She wasn’t looking that way because the commercial bike wasn’t supposed to be there. I wondered for a split second what possessed her to let her guard down like that. This is Nigeria. What worked the way it was supposed to? Why would you expect anyone to obey road and traffic rules? Weird. She was totally oblivious, and was going to get hit by the bike. And everything was slow, or rather, still – like in a mannequin challenge.

I didn’t always think myself a hero, but in that moment, I felt it. I launched myself at her, trying to push her out of the path of the speeding bike. I was in the air, then everything unfroze. My hand shoved her away. But I was now fully in the path of the bike. I was completely airborne. In front of my face was a women’s fashion store. What a thing to see before you die. Shouldn’t my life be flashing before my eyes? Well it had been an unmemorable life thus far. That would have been a boring last thing to see, scenes of my uneventful life. But instead, I saw women’s clothes, which wasn’t any more exciting – women’s clothes worn by a mannequin. I looked at the face, the eyes. It seemed to suck me in. Then the bike hit me. The force was crushing. I felt myself hit the concrete. Snapping, its back tire ran my skull over, then, darkness.

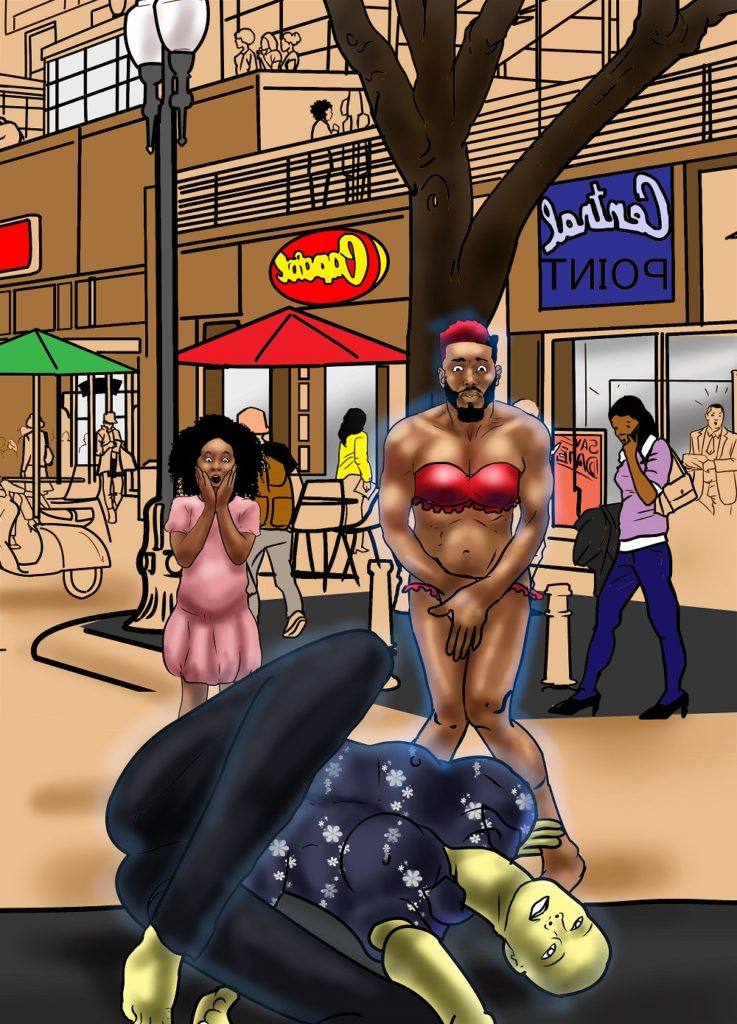

I woke up in a store, wearing women’s clothes. The sales girl burst out screaming. I later walked out to find a crushed mannequin wearing my clothes on the road. The bike man had sped off without stopping. Typical, I thought, standing there in a woman’s pant and bra.

They later called it a prank, but I knew better.

I was standing at the top of the senate building of the University of Lagos with a naked female mannequin. I was over ten floors high. I wore the mannequin clothes and tied it to a pole there. I wasn’t sure how this worked yet (or if it worked at all), but that was why I was here – to run some tests. I had developed powers late, but they had come. Better late than never as they say. Though I say better late than late. The power had come not in the ways I expected it. It hadn’t been a radioactive spider biting me or an explosion in a lab from an experiment. I was a law student anyway, what would I be doing in a lab. I would just get myself burnt for nothing. It had happened, a little unorthodoxly, but it was what I wanted. No more uneventful life. With my new mannequin powers, the possibilities were limitless. I could do some espionage, infiltrate, and obtain valuable information even if I didn’t think much of my fighting abilities. Something like Antman. It wasn’t what I would have chosen, but it was something. So the mannequin was tied, wind wouldn’t blow it/me off. I figured I could shift my consciousness into the mannequin and it into my body and the transference would end once it was destroyed.

I watched recent superhero movies and read enough fantasy novels to know how this worked. A leap of faith, like in Into the Spiderverse. Here I was, set to take a literal leap of faith. That moment you were in danger was when your power activated. It had activated already. But I needed to be sure again. I stood at the edge and turned around. I was naked. I looked at the mannequin. I had chosen female because the first one had been female. I felt more connected to the female mannequin. I hope that doesn’t sound creepy. I was about to connect with my inner woman. That definitely sounded creepy, especially being naked as I was, and staring at a female mannequin wearing my clothes. Leap of faith, right? I looked at it one last time then dove over the edge.

The rush, it was exhilarating. I should change now. Then I realized something was wrong. This hadn’t happened the last time. My life was flashing before my eyes.

He has guest-edited and co-edited several publications, including The Selene Quarterly, Invictus Quarterly and the Dominion Anthology.

He is a member of the African Speculative Fiction Society, Codex, BFA, the BSFA, HWA and the SFWA.

You can find out more about him on his website, and read his novella from the Dominion Anthology for free here https://ekpeki.com/2020/08/24/ife-iyoku-tale-of-imadeyunuagbon/

You can also find him on Twitter at https://www.twitter.com/penprince_nsa

[…] “The Mannequin Challenge” by Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki […]

[…] The winner of the 2019 Nommo Award for Best Short Story and the 2021 Nommo Award for best novella for Ife-Iyoku: The Tale of Imadeyunuagbon, available in Dominion An Anthology of Speculative Fiction From Africa and the African Diaspora, edited by Zelda Knight and Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki. ‘The Witching Hour’ won the Nommo award for best short story in 2019. Here is another story of his, ‘The Mannequin Challenge’ […]